Leen Helmink Antique Maps

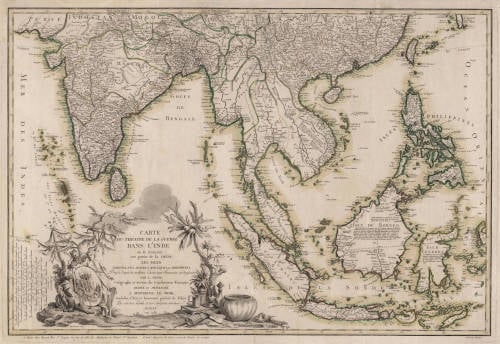

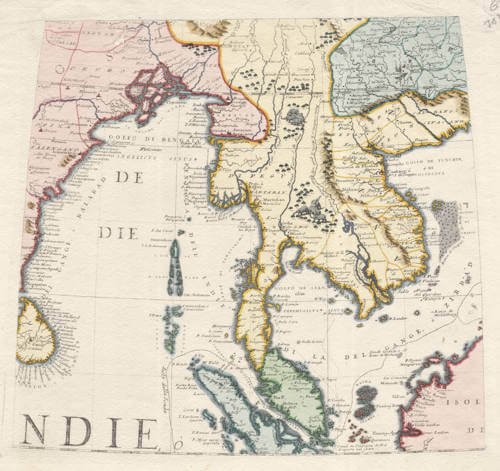

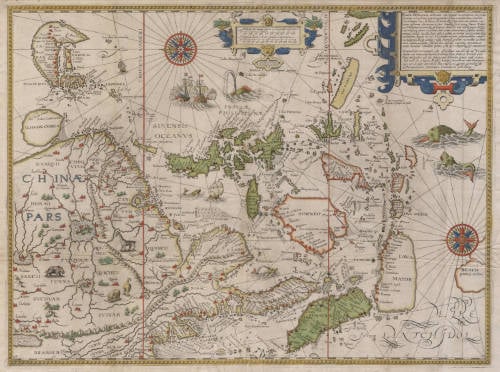

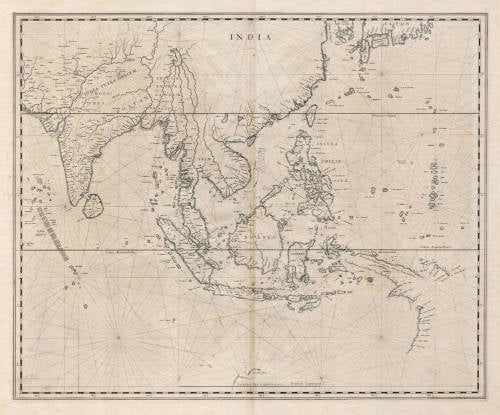

Antique map of New Guinea and the Solomon Islands by Jodocus Hondius Jr

The item below has been sold, but if you enter your email address we will notify you in case we have another example that is not yet listed or as soon as we receive another example.

Stock number: 19723

Zoom ImageCartographer(s)

Title

Nova Guinea et Ins. Salomonis

First Published

Leiden, 1618

This Edition

1618 first edition

Size

8.4 x 12.4 cms

Technique

Condition

mint

Price

This Item is Sold

Description

One of the earliest maps dedicated to the region, preceded only by the 1593 map by de Jode and the 1598 Langenes/Kaerius map, a map that in turn was copied from the illustrious 1592-92 Plancius Spice map.

The map covers New Guinea, the Solomon Islands (Insulae Salomonis), and part of the Southern Continent. The map is engraved by Jodocus Hondius Jr, for his 1618 reissue or Bertius' miniature atlas Caert Thresoor, a succesful project first issued by Barent Langenes in Middelburg and Cornelis Claesz in Amsterdam. Jodocus Hondius aded and replaced dozens of maps for his version of the atlas.

This New Guinea map is of particular interest, because it suggests the early Dutch knowledge of Torres' 1606 discovery of the strait under New Guinea, a fact that is recounted in several early Dutch sources, and was common knowledge with Dutch merchants who did frequent business in Lisbon.

Unfortunately, all VOC expeditions failed to find the western entrance of the strait, despite the explicit instructions to do so. The VOC was very disappointed about not finding this strait, often criticizing their explorers, because it was considered a strategic gateway into the Pacific Ocean leading to the rich Spanish colonies in South America, for business or conquest.

Rarity

The map is of exceptional rarity, appearing in only three editions of the Caert Thresoor.

Significance

The map is of highest significance to Australia, redefining the southern continent as a separate landmass instead of part of New Guinea, and suggesting Dutch knowledge of Torres' discovery of a strait.

Condition description

Strong and even imprint from the first 1618 Latin edition. No restorations or imperfections. Clean paper with wide margins. In breathtaking original colour, from a rare deluxe edition of the atlas. Best imaginable copy of this highly significant map of the area, by one of the greatest cartographers of the day.

Jodocus Hondius (1563-1612)

Jodocus Hondius II (son) (1594-1629)

Henricus Hondius (son) (1597-1651)

Jodocus Hondius the Elder, one of the most notable engravers of his time, is known for his work in association with many of the cartographers and publishers prominent at the end of the sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth century.

A native of Flanders, he grew up in Ghent, apprenticed as an instrument and globe maker and map engraver. In 1584, to escape the religious troubles sweeping the Low Countries at that time, he fled to London where he spent some years before finally settling in Amsterdam about 1593. In the London period he came into contact with the leading scientists and geographers of the day and engraved maps in The Mariner's Mirrour, the English edition of Waghenaer's Sea Atlas, as well as others with Pieter van den Keere, his brother-in-law. No doubt his temporary exile in London stood him in good stead, earning him an international reputation, for it could have been no accident that Speed chose Hondius to engrave the plates for the maps in The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine in the years between 1605 and 1610.

In 1604 Hondius bought the plates of Mercator's Atlas which, in spite of its excellence, had not competed successfully with the continuing demand for the Ortelius Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. To meet this competition Hondius added about 40 maps to Mercator's original number and from 1606 published enlarged editions in many languages, still under Mercator's name but with his own name as publisher. These atlases have become known as the Mercator/ Hondius series. The following year the maps were re-engraved in miniature form and issued as a pocket Atlas Minor.

After the death of Jodocus Hondius the Elder in 1612, work on the two atlases, folio and miniature, was carried on by his widow and sons, Jodocus II and Henricus, and eventually in conjunction with Jan Jansson in Amsterdam. In all, from 1606 onwards, nearly 50 editions with increasing numbers of maps with texts in the main European languages were printed.

(Moreland and Bannister)

Barent Langenes

Langenes was a publisher in Middelburg about whom little is known except that he produced the first edition of a very well known miniature atlas, the 'Caert-Thresoor'. The atlas was the work of Cornelis Claesz in Amsterdam, the foremost publisher of the day. The copperplates were engraved by brothers-in-law Jodocus Hondius and Petrus Kaerius, the most skilled engravers of the day.

The Caert-Thresoor

The Caert-Thresoor, a small atlas of the world in oblong format, appeared in 1598; thereby, its publishers wrote a new page in the history of atlas cartography. The preparations for this prototype of the new generation of Dutch pocket atlases began around 1595. At that time, Cornelis Claesz commissioned the skilled engravers Jodocus Hondius and Pieter van den Keere to engrave the maps. An unnamed young writer and poet - in Burger's opinion, it was Cornelis Taemsz of Hoorn - was called upon to write the accompanying text. Claesz wanted his Caert-Thresoor to outshine the similar small world atlases that had been produced thus far in Antwerp. In this way, he set out to spark interest in and knowledge of geography among the public at large in the Northern Netherlands. In view of the various reprints, editions, and adaptations of this work in Dutch, French, and Latin, obviously the Amsterdam publisher was quite successful in that endeavor.

Even prior to the publication of the little atlas, Cornelis Claesz used the maps that had been prepared in a number of his books, where they served as title vignettes and illustrations in the text. The earliest of these books dates from 1596. Ultimately, the Caert-Thresoor contained 169 maps, engraved in the superb and clear style of the brothers-in-law Hondius and Van den Keere. The text accompanying the maps runs over two volumes, comprising 462 respectively 196 numbered pages. The earliest known edition of the Caert-Thresoor bears the imprint of a printer from Middelburg, Barent Langenes, and indicates that the work was also available from Cornelis Claesz. However, Langenes should only be considered a co-publisher. Even though the dedication to the States of Zeeland bears his signature, he had apparently played only a temporary and minor part in the production process. The publication of the Caert-Thresoor required large, long term investment on the part of Cornelis Claesz, making the financial support and help of others very welcome. Indeed, the preface contains an ode in praise of the Caert-Thresoor and its publisher Cornelis Claesz, along with a note that he had been the driving force behind the project as well as its initiator. From the subsequent edition (1599) onward, only the Amsterdam imprint is given: Tot Amsterdam, By Cornelis Claes. opt water, int Schrijfboeck.

The pocket atlases that were produced in Antwerp remained to a large extent simplified smaller-scale versions of Ortelius's Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Meanwhile, the Caert-Thresoor broke away from this folio atlas and conformed less strictly to the structure and layout of that atlas. Production of the Caert-Thresoor moved in a new direction by including much new material that had been collected in the 1590s in Amsterdam. This material was based partly on Portuguese information and knowledge, partly on that derived from Dutch voyages for trade or discovery. The revisions showed up mainly in the second book, which should be seen as a kind of up-to-date supplement. This part covers the non-European countries. Here one finds, among other things, detailed maps of the Philippines and the archipelago of the East Indies. The maps were taken directly from the map that Jan Huygen van Linschoten made in 1595. Only the map of Java was taken from Plancius's map of the Moluccas. The detailed maps of places in the Indian Ocean derive mainly from Van Linschoten's map of the northern Indian Ocean. The model for the bird's-eye view of Moçambique Island was the engraving in Van Linschoten's Itinerario (1596). Furthermore, the print showing the shipwreck of the Portuguese vessel the S. Jacobus on the shallows known as the Baixos de Iudia in the Strait of Moçambique was copied from Plancius's map of Southern Africa. Plancius's maps also served as models for other maps in the Caert-Thresoor. For example, the Canary Islands, the detailed map of Tercera, and the Cape Verde Islands were copied from them. The small map of Newfoundland is a section of Plancius's map of the North Atlantic Ocean. And the little map of the Strait of Magellan is an unaltered section of Van Linschoten's map of South America.

These are merely a few examples of the sources that were used. The fact that the publishers did not hesitate to use Plancius's and Van Linschoten's maps - in fact, they copied a great deal 'literally' without citing the authors' names - supports the assumption that the atlas was produced by someone very close to these sources. Did not Cornelis Claesz act as publisher for both Plancius and Van Linschoten after all? The last map that appears in the Caert-Thresoor shows the results of Jan Huygen van Linschoten's second voyage in search of a Northeast Passage. The map depicts the seven ships that sailed from Holland and had been in the Kara Sea in 1595. The accompanying text gives a brief report of the two first arctic voyages. In few words, the author reports that the third voyage had not yet been completed, the ship De Rijp had returned but the ship under the command of Willem Barentsz had not yet done so. This small map and the accompanying text were apparently added as the very latest news after the atlas was already complete. However, its value as a source of current information was apparently undermined by the long duration of the printing process for the Caert-Thresoor. Strangely enough, the atlas does not go any deeper into the results and adventures of the third voyage. This is striking, since the members of Barentsz's crew who survived had returned to Amsterdam in the autumn of 1597, while Langenes's dedication was not written till 20 May 1598.

The Caert-Thresoor enjoyed widespread interest, and commercially it did not do Cornelis Claesz any harm. Under his direction, editions appeared in Dutch (1598, 1599, and 1609), French (c.1600 and 1602), and Latin (1600, 1602/03, and 1606). But even after he died, the work still went through a number of editions at different publishing houses. From the Dutch edition of 1599 onward – influenced by the criticism of Paullus Merula - most of the maps were provided a latitude scale. In 1600, a French and a Latin edition appeared. Cornelis Claesz called upon Aelbert Hendricksz in The Hague to print the French edition on the basis of a translation by I. de la Haye, who was a rector and clergyman in Kampen. But for the Latin edition, the production again took place in Amsterdam, though this time in collaboration with a publisher in Arnhem, Jan Jansz. For that edition, the scholar Petrus Bertius (1565-1629) made a completely new geographical description of the whole world. Moreover, the maps then served as illustrations, unlike previous editions in which the text was meant to explain the maps. In 1609, the Caert-Thresoor appeared in a new Dutch version, prepared by the author and poet Jacobus Viverius (1571/72-c.1636). The starting point was the original base text taken from the earlier Dutch editions of 1598 and 1599, which were then partly revised in light of Petrus Montanus's text in Mercator's Atlas Minor (1607).

(Schilder)

THE CAERT-THRESOOR BY BARENT LANGENES AND CORNELIS CLAESZ.

The Caert-Thresoor of 1598 set a new standard for minor atlases. Scholars like Petrus Bertius and Jacobus Viverius edited the text. The small maps are extremely well engraved; they are neat and clear and elegantly composed. They served many purposes in other books published in Amsterdam. Their contents reflect the level of cartography in Amsterdam at the turn of the century, where up-to-date information on newly discovered regions was readily available. The Caert-Thresoor is a collection of maps to which the text was adapted and not the other way around as is the case with many geographical studies.

Its success must have prompted Jodocus Hondius to publish a reduced edition of Mercator's Atlas in 1607.

The first edition was published in 1598 by Barent Langenes, bookseller and publisher located in De Vier Winden in Middelburg (1597-1605). Little is known about Langenes, except that he published some travel descriptions. As is stated on the title page, the edition was also sold by Cornelis Claesz, in Amsterdam. All later editions were published by Claesz. and his successors.

However, in the "Ode", a laudatory poem in 11 strophes, only “Claessoon” is credited for the work. Moreover, in 1605 Paullus Merula wrote in his Cosmographia that Cornelis Claesz. had asked him eight years before to make a Latin translation of the Caert-Thresoor, which Claesz, had published in the Dutch language.

Merula complained that the maps were not only too small but that they also lacked indications of longitude and latitude (in the first 1598 edition issued by Langenes). Merula considered this kind of work useless. Translating the work of novices (“foetus novorum hominum”) into Latin was just a job and added nothing to his scholarly work. Claesz. persisted and asked Merula if he would write a complete new text after the co-ordinates were added to the maps. Merula conceded and would write a completely new text to the maps. Despite this agreement, Merula continued, Bertius had already translated and enlarged the text, which was quite satisfying for him.

Only nine copies of the 1598 first edition by Langenes are known.

(van der Krogt)

Petrus Plancius (1552-1622)

Born as Peter Platevoet in Flanders, Petrus Plancius studied abroad and became a theologian and a mapmaker.

He produced some globes and maps, including a well-known world map in 1592. He had a great influence on the Dutch Asian expeditions.

Early Years

Peter Platevoet was born in 1552 in the Flanders village of Dranouter. Little is known about his childhood, but it seems that his parents became Protestants. Platevoet studied theology, history, and languages in Germany and England. In England he probably learned about mathematics, astronomy, and geography. When he was older, Platevoet Latinized his name, as was the custom among savants at that time.

In 1576 he became a preacher in West-Flanders, a province in Belgium, and later that year he went to Mechelen, Brussels, and Louvain. In the 1580s he stayed in Brussels for a long time, but when the city surrendered to the duke of Parma, King Philip II of Spain’s governor-general in the Netherlands, in 1585 Petrus Plancius fled to the north. He lived in Amsterdam and became a pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church. From December 1585 until his death on 15 May 1622, he fulfilled his job as preacher. Plancius was a fervent Contra-Remonstrant and discussed many theological issues.

In addition to his thorough knowledge of the Holy Bible, he was well-grounded in the study of cosmography, geography, and cartography. He was not only one of the most talked-about preachers in the Dutch republic, but also one of the important mapmakers of his time.

Early Publications

Petrus Plancius was the first caert-snyder (map cutter) in the Dutch republic to produce waxed grid maps. Therefore, on 12 September 1594 he received a patent for the publication and distribution of the world map for twelve years from the States-General. He was, together with the Flemish engraver and map-maker Jodocus Hondius and the brothers Van Langren, one of the first makers of celestial globes in the Netherlands. His first globe was produced in 1589, a revision of an earlier celestial globe. Among his revisions were four additions to the southern sky: the two Magellanic Clouds (they were unnamed on the globe) and two new constellations, Crux and Triangulus Antarticus. Their positions were taken from reports of explorers.

In 1590 Petrus Plancius made five terrestrial maps for a Dutch edition of the Holy Bible. Two years later he made a well-known world map: Nova et exacta terrarum orbis tabula geographica ac hydrographica (New and exact geographical and hydrographical map of the world). This map contained celestial planispheres in the upper corners on which he added two additional constellations.

Asian Expeditions

Petrus Plancius was one of the driving forces behind the first Dutch expeditions to Asia, assisting with preparations and providing instruction. To avoid encounters with Spain and Portugal, which were already sailing to the East Indies around southern Africa, Plancius decided to try a northeast route around Asia. He supplied maps for the voyage and advised the fleet commander, Willem Barents, in celestial navigation. The northeast voyages of 1594 and 1595 were failures, but a third attempt was made in 1596. It was on that last expedition that Barents’s ship got stuck in the polar ice, and the crew had to spend the winter in Nova Zembla, an island northwest above Russia, in what came to be called the Barents Sea. Late in the spring of the next year, the crew was able to sail south in two small boats. Barents died on the return voyage; the survivors arrived at Amsterdam in November 1597, not having found a northeast passageway.

In 1595, together with Barents, Plancius published a book titled Nieuwe Beschrijvinghe ende Caertboeck van de Middelandtsche Zee (New description and map book of the Mediterranean Sea). In this work he designed a map that was engraved by the well-known globe- and map-maker Hondius.

Because the northeast sea route around Asia did not seem very promising, even before the third voyage a group of Dutch merchants had financed a southern expedition. Plancius again helped with the planning and used the opportunity to conduct scientific research. A theory in the late sixteenth century claimed that a compass needle’s variation from north (its declination) would enable one to determine longitude. Plancius developed his own theory to ascertain longitude at sea by means of magnetic variation. To test that theory during the southern voyage, Plancius taught junior merchant Frederik de Houtman how to measure and record compass declinations. It is known that the method developed by Plancius was used from 1596 onward by mariners.

Plancius also used the voyage to discover southern stars that were not visible from Europe. He taught navigators, especially Pieter Dircksz Keyser, but also other sailors, how to measure star positions with an astrolabe and instructed them to chart the southern sky. From ship records of 1596 it is known that the astrolabe was used to measure the declination of the southern stars.

The Dutch southern expedition, known as the Eerste Shipvaart, or First Voyage, set sail from the port of Texel in April 1595. It reached the East Indies in 1596 and returned to Texel in August 1597. Plancius asked Keyser, the chief pilot on the Hollandia, to make observations to fill in the blank area around the south celestial pole on European maps of the southern sky. Keyser died in Java the following year, but his catalog included 135 new stars arranged in twelve new constellations. Most of them were invented to honor discoveries by sixteenth-century explorers. They were first published on a 1598 celestial globe made by Hondius.

After the foundation of the VOC (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or East India Company) in 1602, Plancius became its first mapmaker. During the first quarter of the seventeenth century, he seemed more interested in preaching than in cartography and cosmography. But still, some of his maps were published during that time. In 1607 he produced a large revised world map. In 1612 he created a celestial globe, and later he designed an Earth and another celestial globe (1614 and 1615), both brought out by the well-known publisher Petrus Kaerius. His contemporaries described him as one of the greatest geographers of his time.

Bibliography

A complete bibliography of Plancius’s work, with descriptions of much of his maps and publications, is Günter Schilder, Monumenta Cartographica Neerlandica, Vol. VII, Cornelis Claesz (c. 1551–1609): Stimulator and Driving Force of Dutch Cartography, Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands: Canaletto/Repro-Holland, 2003.

(encyclopedia.com)