Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Antique map of the World by Schedel / Ptolemy

The item below has been sold, but if you enter your email address we will notify you in case we have another example that is not yet listed or as soon as we receive another example.

Stock number: 18648

Zoom ImageDescription

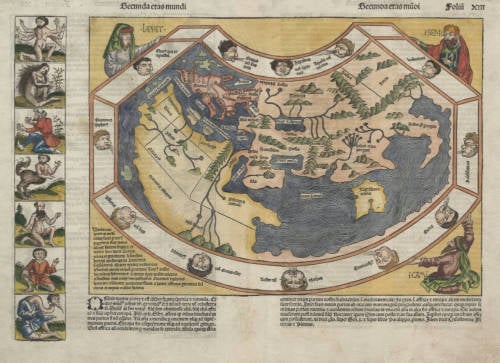

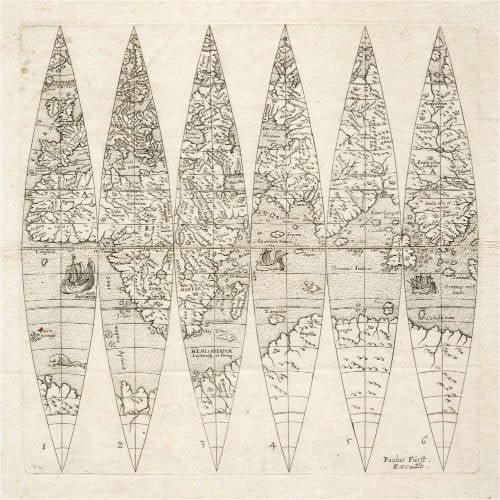

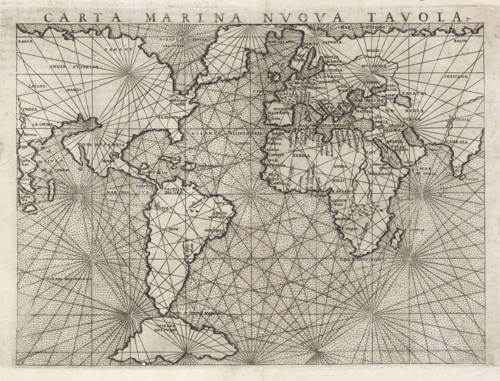

Hartmann Schedel's fantastic incunabula world map, after Ptolemy, cut by Michael Wohlgemut.

Condition

Strong and even imprint of the woodblock. Minor paper restoration in lower centrefold, outside the printed area. This is always the case because the map was stitched/sewn into the book, instead of attached on a stub. This example in rare original color. Excellent collector's condition.

"The last of the Ancient Worlds. A famous wood-cut map featuring an outdated Ptolemaic world with a land-locked Indian Ocean with flanking portraits of Noah's sons - Japhet, Shem and Ham. The bizarre figures outside the map but on the same printed page add to the curious nature of this sought-after piece."

(Potter).

"The renowned Nuremberg Chronicle [...] is one of the great books of the Renaissance [...]. The World map is undoubtedly one of the most curious of any and is really the last pre-Columbian view of the World."

(Potter).

"The Nuremberg Chronicle, as this compendium is popularly known, was one of the most remarkable books of its time. The text is an amalgam of legend, fancy, and tradition interspersed with the occasional scientific fact or authentic piece of modern learning. The many illustrations include two maps - one map of the world and one of Northern Europe - together with views of the principal cities, and a host of repeated decorative woodcuts. Hartmann Schedel, a physician of Nuremberg, was the editor-in-chief; the printer was Anton Koberger, and among the designers the most famous were Michael Wohlgemut and Hanns Pleydenwurff, masters of the Nuremberg workshop where Albrecht Dürer served his apprenticeship.

The world map is a robust woodcut taken from Ptolemy without great attention to detail. The border contains twelve dour windheads while the map is supported in three of its corners by the solemn figures of Ham, Shem, and Japhet taken from the Old Testament.

What gives the map its present-day interest and attraction are the panels representing the outlandish creatures and beings that were thought to inhabit the further-most parts of the earth. There are seven such scenes to the left of the map and a further fourteen on its reverse. Pliny, Pomponius Mela, Solinus, and Herodotus' Fables have been the sources for many of these mythological creatures; others were doubtless born of medieval travellers' tales.

Among the scenes are a six-armed man, possibly based on glimpses of a file of Hindu dancers so aligned that the fromt figure appears to have multiple arms; a six-fingered man, a centaur, a four-eyed man from the Simien Mountains, a cyclops, one of the men whose heads grow beneath their shoulders, one of the crook-legged men who live in the desert and slide along instead of walking; a strange hermaphrodite, a man with one giant foot only (stated by Solinus to be used as a parasol but more likely an unfortunate sufferer from elephantisis), a man with a huge underlip (doubtless seen in Africa), a man with waist-length hanging ears, and other frightening and fanciful creatures of a world beyond.

The first edition of the Nuremberg Chronicle in July 1493 was in Latin and there was a reprint with German text in December of the same year."

(Shirley).

"Asia, like Africa, was supposed to be full of bizarre humanoid creatures. Such legendary beings from ancient cosmographies were given new life in printed books like Hartmann Schedel's 'Nuremberg Chronicle' of 1493. There were, in 'eastern parts', little horned men, bird men, Scythian 'hippopeds', and bald but bearded ladies - all faithfully and graphically illustrated in handsome woodcuts."

(Toolet & Bricker).

"Among them is one of those curiously afflicted people of India with only one leg. The size of his foot compensates, however; it makes a good sunshade. There is a cruelly taloned Scythian gryphon, here menaced by hunters. And there are a headless race of men with faces set into their chests and hill-men with dogs' heads who 'barked for speech'."

(Tooley & Bricker)

For classical sources of some these creatures see

- "umbrella-foot" man

(Pliny Historia Naturalis VII.2: ".. because in the hotter weather they lie on their backs on the ground and protect themselves with the shadow of their feet ..")

- person with dog's head

(Strabo Geographia 1.2: ".. men who are half dog ..")

- creatures having no heads but face on their breast

(Strabo Geographia 1.2: ".. men with eyes in their breasts ..").

Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514)

Nuremberg Chronicle 1493

Amongst all the magnificent books printed in the fifteenth century – which are known as incunables – one stands out as being the finest illustrated topographical work of the period: the Liber Chronicarum or Nuremberg Chronicle. Published by Hartmann Schedel and printed by Anton Koberger in July 1493 it contained a total of 1,809 woodcuts which include a Ptolemaic world map, a 'birds-eye' map of Europe and the first known printed view of an English town. These woodcuts were made by Michael Wohlgemut (Wolgemut) (1434-1519), and his son-in-law, Wilhelm Pleydenwurff. Wohlgemut was Dürer's tutor between 1486 and 1490.

Apart from its general interest as a very early descriptive topographical work, the Nuremberg Chronicle is also, by virtue of its date of publication, an historical document of the greatest importance. Issued seven months after Columbus landed in the New World, the Chronicle presents us with a 'lasť view of the known medieval world as seen by the peoples of Western Europe. Within a few years new editions were being issued incorporating news of the successful Atlantic voyages on the American continent; discoveries which proved to be key factors in the complex problems of mapping the modern world as we know it.

(Moreland and Bannister).

Claudius Ptolemy (c.100 - c.170)

Ptolemy, Latin in full Claudius Ptolemaeus was an Egyptian astronomer, mathematician, and geographer of Greek descent who flourished in Alexandria during the 2nd century AD. In several fields his writings represent the culminating achievement of Greco-Roman science, particularly his geocentric (Earth-centred) model of the universe now known as the Ptolemaic system.

Virtually nothing is known about Ptolemy’s life except what can be inferred from his writings. His first major astronomical work, the Almagest, was completed about 150 ce and contains reports of astronomical observations that Ptolemy had made over the preceding quarter of a century. The size and content of his subsequent literary production suggests that he lived until about 170 AD.

Astronomer

The book that is now known as the Almagest (from a hybrid of Arabic and Greek, “the greatest”) was called by Ptolemy Hē mathēmatikē syntaxis (“The Mathematical Collection”) because he believed that its subject, the motions of the heavenly bodies, could be explained in mathematical terms.

Mathematician

Ptolemy has a prominent place in the history of mathematics primarily because of the mathematical methods he applied to astronomical problems. His contributions to trigonometry are especially important. For instance, Ptolemy’s table of the lengths of chords in a circle is the earliest surviving table of a trigonometric function. He also applied fundamental theorems in spherical trigonometry (apparently discovered half a century earlier by Menelaus of Alexandria) to the solution of many basic astronomical problems.

Among Ptolemy’s earliest treatises, the Harmonics investigated musical theory while steering a middle course between an extreme empiricism and the mystical arithmetical speculations associated with Pythagoreanism. Ptolemy’s discussion of the roles of reason and the senses in acquiring scientific knowledge have bearing beyond music theory.

Geographer

Ptolemy’s fame as a geographer is hardly less than his fame as an astronomer. Geōgraphikē hyphēgēsis (Guide to Geography) provided all the information and techniques required to draw maps of the portion of the world known by Ptolemy’s contemporaries. By his own admission, Ptolemy did not attempt to collect and sift all the geographical data on which his maps were based. Instead, he based them on the maps and writings of Marinus of Tyre (c. 100 ce), only selectively introducing more current information, chiefly concerning the Asian and African coasts of the Indian Ocean. Nothing would be known about Marinus if Ptolemy had not preserved the substance of his cartographical work.

Ptolemy’s most important geographical innovation was to record longitudes and latitudes in degrees for roughly 8,000 locations on his world map, making it possible to make an exact duplicate of his map. Hence, we possess a clear and detailed image of the inhabited world as it was known to a resident of the Roman Empire at its height—a world that extended from the Shetland Islands in the north to the sources of the Nile in the south, from the Canary Islands in the west to China and Southeast Asia in the east. Ptolemy’s map is seriously distorted in size and orientation compared with modern maps, a reflection of the incomplete and inaccurate descriptions of road systems and trade routes at his disposal.

Ptolemy also devised two ways of drawing a grid of lines on a flat map to represent the circles of latitude and longitude on the globe. His grid gives a visual impression of Earth’s spherical surface and also, to a limited extent, preserves the proportionality of distances. The more sophisticated of these map projections, using circular arcs to represent both parallels and meridians, anticipated later area-preserving projections. Ptolemy’s geographical work was almost unknown in Europe until about 1300, when Byzantine scholars began producing many manuscript copies, several of them illustrated with expert reconstructions of Ptolemy’s maps. The Italian Jacopo d’Angelo translated the work into Latin in 1406. The numerous Latin manuscripts and early print editions of Ptolemy’s Guide to Geography, most of them accompanied by maps, attest to the profound impression this work made upon its rediscovery by Renaissance humanists.

(Britannica)

Related Categories

Related Items