Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Old books, maps and prints by Maarten van Heemskerck

Maarten van Heemskerck (1498-1574)

Maarten van Heemskerck (1498–1574), born Maarten Jacobsz in Heemskerk, North Holland, was one of the most prominent Flemish artists of the 16th century, renowned for his innovative paintings, altarpieces, and engravings that bridged Netherlandish traditions with the influence of Italian Renaissance art. His prolific career, marked by technical mastery and a keen interest in classical antiquity, produced a diverse body of work, including his iconic series of engravings depicting the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Van Heemskerck’s contributions to Northern Renaissance art, particularly through his integration of Italianate styles and his focus on historical and mythological subjects, established him as a pivotal figure in the cultural landscape of the Low Countries.

Born in 1498 to a farmer, Jacob Willemsz van Veen, Van Heemskerck initially trained under Cornelis Willemsz in Haarlem before apprenticing with the renowned painter Jan Lucasz in Delft around 1527. His early exposure to the works of Jan van Scorel, a leading Dutch artist who had studied in Italy, profoundly shaped his artistic trajectory. In 1532, Van Heemskerck embarked on a transformative journey to Italy, spending four years in Rome and other cities. There, he immersed himself in the study of classical antiquities, Renaissance masters like Michelangelo and Raphael, and architectural marvels such as the Colosseum. His meticulous sketches of Roman ruins, sculptures, and contemporary artworks, including studies of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, informed his later compositions and fueled his fascination with the grandeur of the ancient world.

Upon returning to Haarlem in 1536, Van Heemskerck joined the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke and established himself as a leading artist. His paintings from this period, such as the Ecce Homo altarpiece (1544, Warsaw) and the Family Portrait (c. 1530, Kassel), demonstrate a synthesis of Netherlandish detail with Italianate monumentality, characterized by muscular figures, dramatic compositions, and vibrant colors. His altarpieces, often created for churches in Haarlem and Amsterdam, showcased his ability to convey religious narratives with emotional intensity and architectural sophistication, reflecting his Italian experiences. Van Heemskerck’s versatility extended to portraiture and genre scenes, but his engravings, produced in collaboration with publishers like Hieronymus Cock, brought him widespread fame.

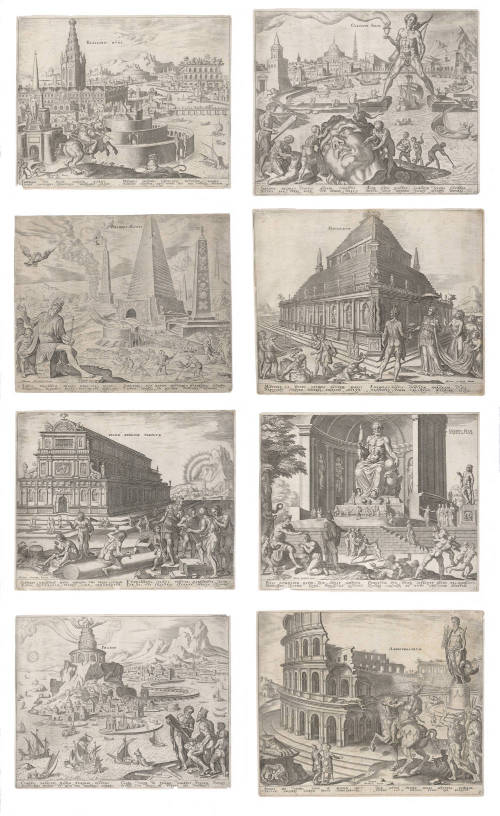

Among Van Heemskerck’s most celebrated works is his series of engravings titled The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, created in 1572 and published by Philips Galle in Antwerp. This set of eight prints—one for each of the seven wonders plus an extra plate of the Colosseum that van Heemskerck had visited—represents a landmark in the visualization of classical antiquity. The wonders depicted include the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the Colossus of Rhodes, and the Lighthouse of Alexandria. Each engraving is a vivid reconstruction of these lost monuments, blending historical imagination with artistic invention. Van Heemskerck drew on ancient texts, such as those by Herodotus and Pliny the Elder, as well as his own observations of Roman ruins, to create detailed, atmospheric compositions that captivated contemporary audiences.

The Seven Wonders series is notable for its technical and conceptual sophistication. Each print features a monumental structure set within a dynamic landscape, populated by figures in classical attire that evoke the era of the wonders’ construction. For instance, the Colossus of Rhodes depicts a towering statue straddling the harbor, its form inspired by Italian sculptures, while the Hanging Gardens of Babylon imagines lush terraces teeming with exotic flora. The engravings are accompanied by Latin inscriptions that provide historical context, reflecting Van Heemskerck’s scholarly approach. The series not only popularized the concept of the seven wonders in European art but also served as a meditation on human achievement, impermanence, and the passage of time—a theme resonant in the post-Reformation Netherlands, where Van Heemskerck worked amidst religious and political upheaval.

Van Heemskerck’s engravings were widely disseminated, thanks to the burgeoning print market, and influenced artists across Europe. His collaboration with professional engravers ensured that his designs were rendered with precision, making his work accessible to a broader audience than his paintings. The Seven Wonders series, in particular, became a cultural touchstone, inspiring later artists and antiquarians to explore classical themes. Beyond this series, Van Heemskerck produced numerous other print cycles, including biblical scenes, allegories, and mythological narratives, such as the Triumphs of Petrarch (1565), which further showcased his ability to weave narrative and symbolism.

On a personal level, Van Heemskerck’s life was shaped by both ambition and adaptability. He married twice, first to Maritgen Gerritsdr, who died in 1559, and later to Maria Cornelisdr. His financial success as an artist allowed him to purchase properties in Haarlem and Amsterdam, reflecting his status as a respected citizen. In 1572, amid the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule, Van Heemskerck fled Haarlem for Amsterdam to escape the siege by Spanish forces, demonstrating his resilience in turbulent times. Despite these challenges, he continued to work prolifically until his death on October 1, 1574, in Haarlem.

Van Heemskerck’s legacy endures through his contributions to Northern Renaissance art and his role in popularizing classical themes. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World series remains a testament to his imagination, technical skill, and engagement with the intellectual currents of his time. His ability to merge Netherlandish precision with Italian grandeur not only elevated the status of Dutch art but also paved the way for future generations of artists, including his pupil Dirck Volkertsz Coornhert. Today, his works are housed in major museums, such as the Rijksmuseum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they continue to inspire admiration for their beauty and historical significance.

(Wikipedia)