Leen Helmink Antique Maps

the first intaglio colour printing

Stock number: 19909

Zoom ImageCartographer(s)

Johannes Teyler (biography)

Title

[ Peacock ]

First Published

Nijmegen, 1688

Size

14.5 x 26 cms

Technique

Condition

excellent

Price

$ 950.00

(Convert price to other currencies)

Description

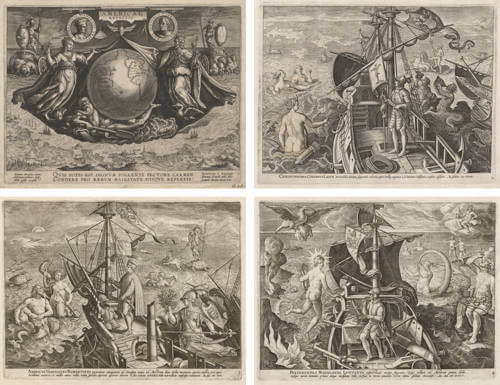

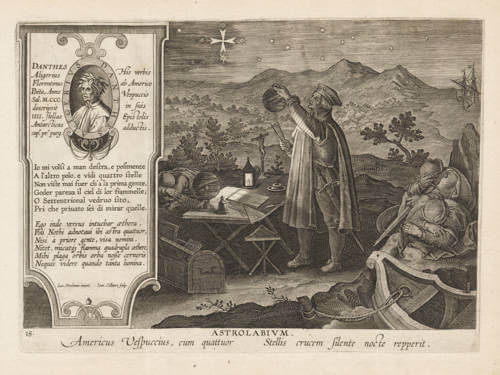

One of the first colour prints ever, produced from copperplate printing à la poupée.

Elegant portrayal of a peacock, produced with Teyler's pioneering use of innovative color printing techniques, notable for its finesse and subtlety, distinguishing him as an early master in the field of color printmaking.

The Colour Prints of Johannes Teyler

Thomas Herbert, 8th Earl of Pembroke (1656/7–1733), wrote captions beneath the prints in an album in his collection demonstrating the ‘first inventors of all the different manners.’

Below a print issued by Johannes Teyler (1648–c.1709) he noted: ‘Mr Tayler a Painter, who improved the printing of Stuffs in Holland’.1 In 1821, Adam von Bartsch stated that ‘Taylor’ was ‘an English engineer under Friedrich Wilhelm I, the Great Elector’. Neither seemed to know his Christian name or the spelling of the surname (often ‘Teiler’). Nevertheless both accurately identified aspects of Teyler’s unusual curriculam vitae and recognised his innovation in colour printing before the elaborate multi-plate printing process developed by Jacob Christoff Le Blon.

The printmakers active in Teyler’s workshop used conventional intaglio techniques, but Teyler refined an unconventional method, printing coloured inks simultaneously to create polychrome images. Some prints feature non-linear, tonal stipple and mezzotint elements, as later found in French eighteenth-century colour printmaking. In only ten years, 1688–97, he created over 600 colour prints (a conservative estimate) that achieved far brighter colours and more naturalistic effects than chiaroscuro woodcuts by exploiting the vibrancy of pigments and whiteness of paper. Their subjects are diverse – birds, butterflies, flowers, vases, portraits, town views – but their printing is consistently professional and tidy, with laboriously handcrafted inking, pointing to a large-scale enterprise. They are not experimental, original artistic statements in the manner of Hercules Segers, but there is an intriguing similarity: Segers ‘painted or printed on his shirts and on the sheets of his bed’ and Teyler printed on textiles. His willingness to go beyond printmaking on paper into, for instance, decorative and applied arts including tapestries and wallpaper, has been little explored. Teyler may have attempted other potentially lucrative endeavours, like illustrating books on natural history considering the many prints of birds, plants and animals, but none seem to have been commercially viable. However, his process was adopted in 1695 by the Amsterdam publishers Gerard Valck, who used it less daringly and less skilfully, and then Petrus Schenck and Carel Allard, who issued similar series of topographical prints in both black and coloured versions.

They are technical tours de force of inking, wiping and printing. The process is laborious, slow and complex, not ‘solid, sure and easy’ as Le Blon wrote. The colours are rubbed on to large expanses of the plate or carefully daubed on smaller areas using stumps of tightly rolled linen, associated with the French term à la poupée. After each application of a colour the plate is carefully wiped so that the lines receive the ink and the plate’s surface is clean. Overly vigorous wiping makes the colour pale (due to insufficient ink) or removes it entirely. Keeping the colours separate is difficult; they bleed together and overlap, which can be observed under magnification. Applying the colour in whirling bands created a marbled effect.

(Simon Turner)

Rarity

All Teyler prints are of exceptional rarity.

Significance

The first intaglio colour printing technique, developed by Johannes Teyler. The prints are characteristic, because all of the copper plates were inked in multiple colours in the so-called a la poupée manner.

For most of the 15th-17th centuries, very limited color printing was attempted as hand-colored pages remained the preferred method of pictorial representation. As various printing techniques spread across Europe, new approaches to color reproduction were tested. Some color illustrations were made using wood blocks.

By the mid-fifteenth century, intaglio engraving emerged as the standard method for printing images in black and white.

Around 1680, a mathematician and engineer from Nijmegen, Holland named Johan Teyler developed a means of dabbing different colored inks into the wells of intaglio plates—originally intended for black-only printing—to make a full-color impression all at one time. Like Fust and Schoeffer’s work, Teyler’s color results were artistically beautiful but could not be developed into a viable commercial process.

Condition description

Very bright printed colours, an excellent copy.

Johannes Teyler (1648–c. 1709)

Johannes Teyler, born on May 23, 1648, in Nijmegen, was a multifaceted figure of the Dutch Golden Age, renowned for his contributions to color printmaking, painting, engraving, mathematics, and philosophy. His father, William Taylor, an English or Scottish mercenary, settled in the Netherlands, adopting the surname Teyler. Operating an inn called ’t Hert opposite Nijmegen’s Grote Markt, William provided a modest upbringing for Johannes, who was born to his second wife, Anna van Haef. The inn, frequented by students from the nearby Kwartierlijke Academie, likely exposed young Johannes to intellectual discussions, shaping his early curiosity.

Teyler’s education began at Nijmegen’s Latin School, where he studied Latin, followed by enrollment at the Kwartierlijke Academie. There, he immersed himself in mathematics and philosophy, writing a dissertation defending Cartesian philosophy, which reflected his alignment with progressive intellectual currents. After his father’s death in 1668, Teyler continued his studies in Leiden, deepening his engagement with Cartesian ideas. In 1670, he secured a position as Professor of Mathematics and Philosophy at Nijmegen, earning respect but facing career limitations due to his controversial philosophical stance, which clashed with traditional academic hierarchies.

Travels and Artistic Development

In 1679, Teyler embarked on an extensive journey through Italy, Egypt, the Holy Land, and Malta, sketching fortifications and honing his artistic skills. His time in Rome was particularly formative, where he joined the Bentvueghels, a Dutch artists’ society. Known by the nickname “Speculatie”—a nod to both his speculative nature and possibly his covert activities as a “speculator” (spy)—Teyler’s integration into this circle underscored his painting and engraving talents. His earlier nicknames, “Ezel” (Donkey) and “Gouden Ezel” (Golden Donkey), hinted at his complex persona and efforts to cultivate favor through generosity.

Returning to the Netherlands in 1683, Teyler settled in Holland, later purchasing a house in Blotinge near Rijswijk. His travels enriched his artistic repertoire, evident in his detailed etchings, such as a colorful view of Nijmegen from the north (c. 1680). His exposure to diverse cultures and landscapes informed the eclectic subjects of his later prints, ranging from mythological scenes to military plans.

Innovations in Color Printmaking

Teyler’s most enduring legacy lies in his pioneering work in color printmaking, particularly the à la poupée technique, which involved inking a single copper plate with multiple colors to produce vibrant, multi-hued impressions. Around 1683–1688, he developed this method, achieving unprecedented technical sophistication. His workshop, active from approximately 1685 to 1697, produced over 400 unique prints, featuring vivid yellows, reds, greens, and blues, with up to ten colors per impression and marbling effects that allowed colors to blend seamlessly. Subjects included classical figures, landscapes, birds, flowers, and military encampments, reflecting both artistic and commercial appeal.

In 1685, Teyler collaborated with Jan van Call, a former student and skilled engraver, to establish a printing workshop in Rijswijk, focusing initially on military-related works. By 1688, he secured a privilege from the Staten van Holland en West-Friesland, protecting his innovative color printing process. Teyler’s printers demonstrated remarkable precision, inking areas as small as 2 mm squared with distinct colors, a feat unmatched by contemporaries. His workshop also experimented with printing on fabric, producing wall hangings and bed hangings, though only four such examples survive. Visitors, including the renowned mathematician Christiaan Huygens, marveled at the workshop’s output, which included prints on linen that served as decorative paintings or wall coverings.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1697, Teyler sold his workshop, and the following year, its inventory—including copper plates, printing presses, and printed fabrics—was auctioned in Rotterdam. Around this time, he traveled to Berlin with Jacob de Heusch, a fellow Bentvueghel, possibly to explore new opportunities. Correspondence with Gottfried Leibniz, a close acquaintance, reveals Teyler’s attempt to secure a professorship in Wolfenbüttel in 1694, though he abandoned the pursuit after discussions with Huygens. His later years remain obscure, with his death estimated between 1697 and 1709, likely in Nijmegen.

Teyler’s influence on printmaking was profound, transforming the market with his colorful, high-quality prints. His à la poupée technique inspired Amsterdam publishers from 1695 to 1710, who produced around 600 additional prints in his style, including illustrations for Cornelis de Bruijn’s Travels (1700). The technique spread to England, Germany, France, and Italy throughout the 18th century, cementing Teyler’s role as a game-changer in print history. Despite his innovations, the labor-intensive nature of his process limited its adoption, as each impression required meticulous hand-inking.

Conclusion

Johannes Teyler’s life was a tapestry of intellectual pursuit, artistic innovation, and adventurous exploration. As a mathematician, philosopher, and artist, he navigated the cultural and intellectual currents of the Dutch Golden Age, leaving an indelible mark through his mastery of color printmaking. His workshop’s output, characterized by technical brilliance and aesthetic diversity, not only enriched the visual culture of his time but also set a precedent for future generations of printmakers. Though his name faded after his death, Teyler’s contributions endure in the vibrant prints that continue to captivate art historians and collectors, a testament to his visionary spirit and interdisciplinary genius.

Sources:

Johan Teyler - Wikipedia

Johannes Teyler and Dutch Colour Prints | Ad Stijnman - Academia.edu

Johannes Teyler (1648–1709?) and Colour Printed Fabric - American Printing History Association

Published: Johannes Teyler and Dutch colour prints, Hollstein

Johannes Teyler — Wikipedia

Johannes Teyler, Part I, Hollstein