Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Unrecorded French Scioto Land Pamphlet

Stock number: 19713

Zoom ImageCartographer(s)

Jean Guillaume Castel

Title

Avis au Public

First Published

Paris, 1791

Size

30.0 x 40.7 cms

Technique

Condition

excellent

Price

$ 1,750.00

(Convert price to other currencies)

Description

Unrecorded French Scioto Land Pamphlet, Paris, 1791.

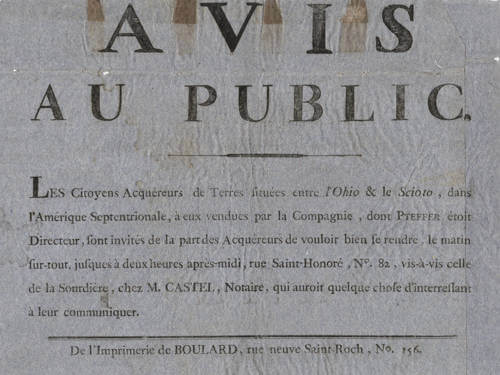

AVIS

AU PUBLIC.

Les Citoyens Acquéreurs, de Terres situées entre l’Ohio & le Scioto, dans l’Amérique Septentrionale, à eux vendues par la Compagnie, dont Pteffer étoit Directeur, sont invités de la part des Acquéreurs de vouloir bien se rendre, le matin sur-tout, jusqu’à deux heures après-midi, rue Saint-Honoré, N°. 82, vis-à-vis celle de la Sourdière, chez M. Castel, Notaire, qui auroit quelque chose d’intéressant à leur communiquer.

De l’Imprimerie de BOULARD, rue neuve Saint-Roch, No. 156.

NOTICE

TO THE PUBLIC.

The Citizen Purchasers of Lands situated between the Ohio & the Scioto, in North America, sold to them by the Company, of which Pteffer was Director, are invited, on behalf of the Purchasers, kindly to present themselves, especially in the morning, up until two o’clock in the afternoon, at rue Saint-Honoré, No. 82, opposite that of the Sourdière, at the office of Mr. Castel, Notary, who would have something of interest to communicate to them.

From the Printing House of BOULARD, rue Neuve Saint-Roch, No. 156.

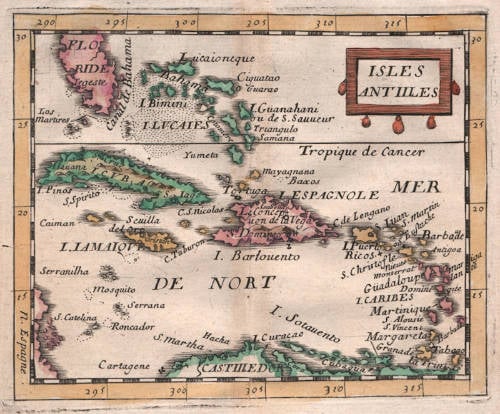

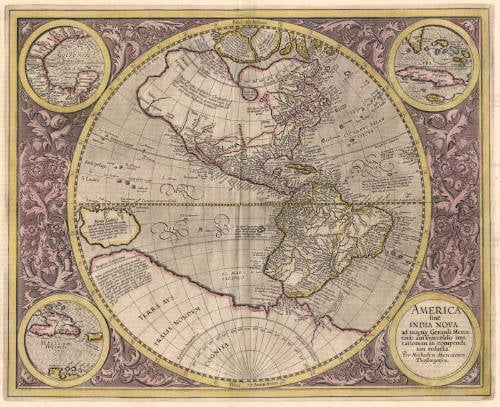

Unrecorded pamphlet titled AVIS AU PUBLIC (Notice to the Public), printed in Paris by the Boulard press at Rue Neuve Saint-Roch No. 156, addresses French citizens who purchased lands "between the Ohio and Scioto Rivers" in North America. These lands were sold by a speculative venture known as the Scioto Company, part of a broader wave of transatlantic land speculation in the late 1780s. The document invites these buyers to present themselves at the office of M. Castel, Notary, located at 82 Rue Saint-Honoré, where they would receive important updates.

The Scioto Company, founded in 1787–1789, was a transatlantic enterprise spearheaded by American financiers such as William Duer and Joel Barlow, along with Scottish economist William Playfair and several French aristocrats and businessmen. It aimed to resell land in the American Northwest Territory to European investors, capitalizing on both the promise of the fertile Ohio frontier and the anxieties of French citizens during the early stages of the Revolution. Thousands of French investors bought shares or deeds, believing they were purchasing titles to new American lands.

However, the Scioto Company never fully secured ownership of the lands it sold, making its promises largely fraudulent. By late 1790, the company collapsed financially, leaving French buyers with worthless papers and causing widespread distress among both those who had invested money and those who had emigrated to America in search of new lives.

The pamphlet references Director Pteffer (likely a misspelling of "Pfeiffer" or perhaps a phonetic rendering of an obscure figure), who served as a leading agent or administrator of the Scioto Company in Paris. While key figures like Barlow and Playfair are well-documented in the company's formation, Pteffer/Pfeiffer appears to have been the local director or representative managing affairs on the ground in Paris, especially as the company began to unravel.

The Notary M. Castel at 82 Rue Saint-Honoré was a registered legal official active between 1786 and 1797, responsible for handling official documentation, contracts, and public notices. His office became the designated point of contact for French land purchasers seeking updates or potential remedies after the collapse of the Scioto scheme. Castel's role would have been to formalize any new legal arrangements, register claims, or disseminate collective information to the aggrieved investors.

The Boulard printing house, active during the revolutionary period, was known for producing a range of political and legal materials. Its involvement situates the pamphlet firmly within the early 1790s revolutionary publishing context.

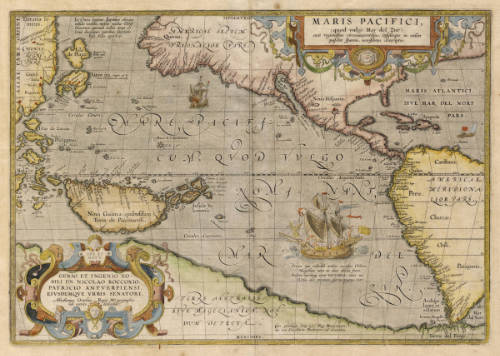

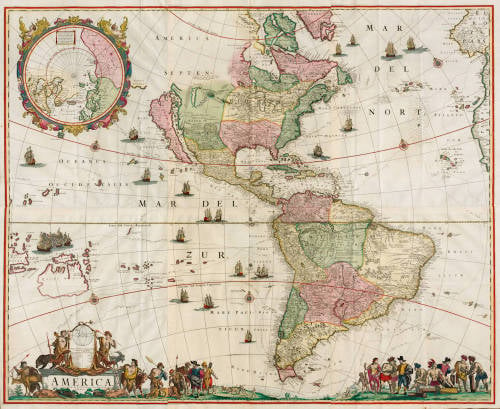

The pamphlet holds important historical value because it bridges the histories of the United States, France, and (indirectly) Canada. For the United States, it reflects the chaotic and speculative nature of early frontier expansion and land sales, which drew European capital but also created international financial and legal entanglements. For France, it reveals the desperation of citizens caught in revolutionary turmoil, seeking security and opportunity across the Atlantic but falling victim to fraud. While not directly tied to Canada, it connects to the broader narrative of French imperial decline in North America, as French hopes shifted southward to American ventures after the 1763 loss of Canada to Britain.

Based on the language (use of "Citoyens" instead of "Messieurs"), the printer's active years, and the historical timeline of the Scioto Company's collapse, the pamphlet was almost certainly printed in late 1791, possibly into early 1792. This coincides with the final attempts by French investors, aided by American and French military figures like Colonel Rochefontaine and General Duportail, to organize compensation or substitute land arrangements for the defrauded buyers. The urgency of the notice suggests it was part of a last-ditch effort to consolidate claims and possibly salvage part of the investors' losses before political conditions in France further deteriorated.

This pamphlet is a rare and valuable artifact documenting the intersection of revolutionary-era French emigration, early U.S. land speculation, and the enduring ripple effects of imperial loss in North America.

Rarity

Unrecorded, only copy known.

Significance

This unrecorded pamphlet is a rare witness to the collapse of one of the first major international land speculation bubbles linking the United States, France, and indirectly Canada.

For the U.S., it reflects how early American lands (the Ohio frontier) became the focus of transatlantic dreams, investment, and ultimately legal troubles, shaping migration and settlement patterns like those at Gallipolis.

For France, it marks the anxiety of Revolution-era citizens seeking refuge and prosperity abroad, only to be defrauded, highlighting the vulnerability of French emigrants and investors during political upheaval.

While not directly tied to Canada, it connects to broader patterns of French Atlantic ambition and loss after the fall of New France, showing how French hopes shifted southward to the young United States when Canadian colonial outlets were lost.

Related Categories