Leen Helmink Antique Maps

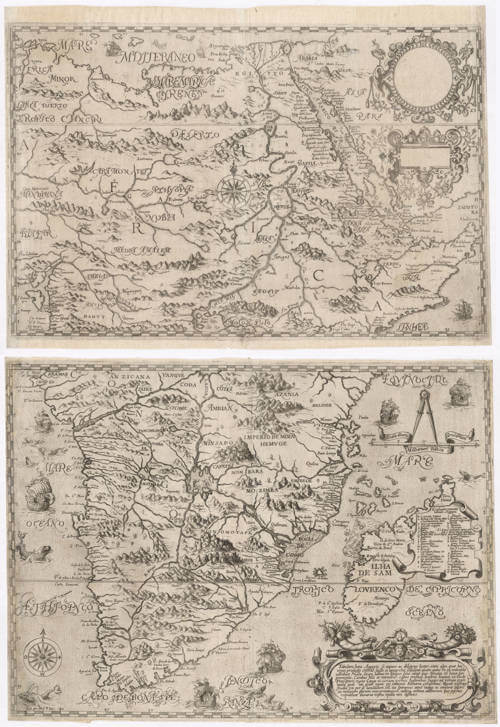

Antique map of Africa by Pigafetta / de Bry / Lopez

Stock number: 19465

Zoom ImageTitle

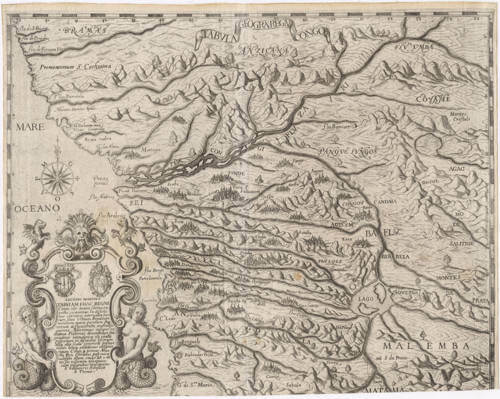

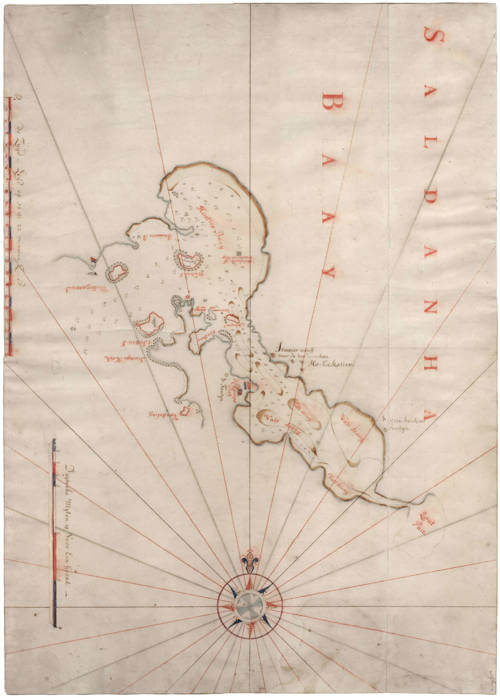

Tabulam Hanc Aegypti, Si aequus ac diligens lector, cum alys…Imperio Ioannis, ut vocat Praesbyteri regno Congo et circum vicinis regionibus ... Vera Desciptio Regni Africani, Quod Tam Abincolis Quam Lusitanis Congus appellatur ...

First Published

Frankfurt, 1598

This Edition

1598

Technique

Condition

excellent

Price

$ 7,500.00

(Convert price to other currencies)

Description

The most important and most accurate map of Africa published in the 16th century and for long after.

The map appears in the rare 1598-99 edition of De Bry's Vera Desciptio Regni Africani, Quod Tam Abincolis Quam Lusitanis Congus appellatur, and is issued in two sheets.

The maps importance is that it rejects the classical Ptolemaic depiction of the interior of Africa, thus being way ahead of it's time.

The map is extremely decorative, with elaborate scrollwork cartouches, swash lettering, sea monsters and numerous Portuguese carracks roaming around Africa to and from the East Indies.

The map is based on the discoveries by the Portuguese merchant Duarte Lopez, a Portuguese trader who had spent twelve years in the Congo. Lopez had hoped that the pope would give him support in his mission to the Congolese, but this was not forthcoming: he returned to Africa, and was not heard from again. Lopez's narrative gives a detailed account of his voyage on his uncle's ship, and the history and geography of the kingdom of Congo and its six administrative regions under the rule of its king (named by Lopez 'Don Alvarez'). The account demonstrates the extent of Portuguese exploration across West Africa in the sixteenth century, of which later explorers were unaware.

Condition

Good early imprints of the copperplate. No restorations or imperfections. Two unjoined sheets as originally published at the time. Excellent collectors' condition.

Theodore de Bry (c.1527-1598)

De Bry was an engraver, bookseller and publisher, active in Frankfurt-am-Main, who is known to have engraved a number of charts in Waghenaer’s The Mariners Mirrour published in London in 1588. In that same year, also in London, an account was published by Thomas Hariot, illustrated by the artist John White, describing Raleigh's abortive attempt to found a colony in Virginia, and this was to be the inspiration for de Bry's major work, the series of Grands Voyages and Petits Voyages. In all, 54 parts of these two works were issued containing very fine illustrations and beautiful, and now very rare, maps, much sought after by collectors.

(Moreland and Bannister)

Filippo Pigafetta (1533–1604)

Filippo Pigafetta (1533–1604) was an Italian mathematician and explorer. He is believed to be a descendant of Antonio Pigafetta, who travelled with Magellan and documented the first circumnavigation of the world.

Pigafetta's Relatione del reame del Congo (A Report of the Kingdom of Congo and of the Surrounding Countries) 1591 was translated into English, Latin (as Regnum Congo), French, Dutch and German. In it Pigafetta explains that he was ordered by Pope Sixtus V to transcribe the account of Duarte Lopez, a Portuguese trader who had spent twelve years in the Congo. Lopez had hoped that the pope would give him support in his mission to the Congolese, but this was not forthcoming: he returned to Africa, and was not heard from again. Lopez's narrative gives a detailed account of his voyage on his uncle's ship, and the history and geography of the kingdom of Congo and its six administrative regions under the rule of its king (named by Lopez 'Don Alvarez'). The account demonstrates the extent of Portuguese exploration across West Africa in the sixteenth century, of which later explorers were unaware.

(Wikipedia)

Duarte Lopez (fl. 1578-1589)

Between 1578 and 1589, the Portuguese merchant Duarte Lopez travelled to Central Africa on the orders of Philip II of Spain (Portugal being under a personal union with Spain) to serve as ambassador to the powerful central African kingdom of Kongo (now northern Angola). Portugal had first made contact with the kingdom in the 1480s, developing a trading relationship in luxury goods including ivory and precious metals and later in the enslavement of Kongo and neighbouring people. This relationship also involved the regular kidnapping of Kongo nobles in return for Portuguese troops and their transport back to Portugal. By 1483, the king (Mwene Kongo) Nzinga a Nkuwu (r. 1470-1509) converted to Christianity and travelled to Portugal to learn the religion, adopting the Christian name João in honour of the Portuguese king, João II (r. 1481-95). Christianity, in the form of Roman Catholicism, soon spread across the kingdom, encouraged in particular by Joao I's successor Afonso I Mvemba a Nzinga (r. 1509-42/3.

Following Afonso I’s death in 1542, Portugal took advantage of instability over the succession, intensified enslavement despite Kongo protests and tried to increase its control over the country. As relations between the two states continued to decline, in 1568, a new dynasty under Alvaro I Nimi a Lukeni lua Mvemba (r. 1568-87) came to power, with Lopez arriving a decade later. In his twelve years in Africa, Lopez made significant observations on Kongo culture and the political situation in the region. He returned to Portugal in 1589 and made overtures to Pope Sixtus V to sponsor a new mission to Kongo. In response, the Pope ordered a transcription of Lopez’s report by the explorer Filippo Pigafetta, which was published in 1591 under the title Relatione del reame del Congo. The book was quickly translated into Latin, English, French, Dutch and German. It provided one of the most detailed accounts of Central Africa available in the sixteenth century. Despite Lopez’s hopes, the Pope did not sponsor a new mission to Africa, leaving him to make his own way back to Kongo, after which nothing more was heard.

Even though Pigafetta’s work was translated into various European languages, by the nineteenth century, his book was forgotten and central Africa became known pejoratively as the ‘Dark Continent’, a region about which nothing was known. This new edition, translated from the Italian by Margarite Hutchinson with a preface by the abolitionist explorer Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, was published in 1881. In her introduction to the work, Hutchinson blamed the loss of knowledge about Kongo and its neighbouring states among readers in Britain on a general disinterest across Europe in Portugal’s colonisation of Africa.

(Hutchinson)