Leen Helmink Antique Maps & Atlases

www.helmink.com

Georg Joachim Rheticus (attributed)

Abraham Ortelius

Caspar Vopelius

[ Untitled ]

Certificate of Authentication and Description

This is to certify that the item illustrated and described below is a genuine antique

map, print or book that was first produced and published in 1564, today 461 years ago.

November 17, 2025

Cartographer(s)

Georg Joachim Rheticus (attributed)

Abraham Ortelius

Caspar Vopelius

First Published

Augsburg, 1564

This edition

only copy known

Size

Ø 43 cms

Technique

Copper engraving

Stock number

19701

Condition

excellent

Description

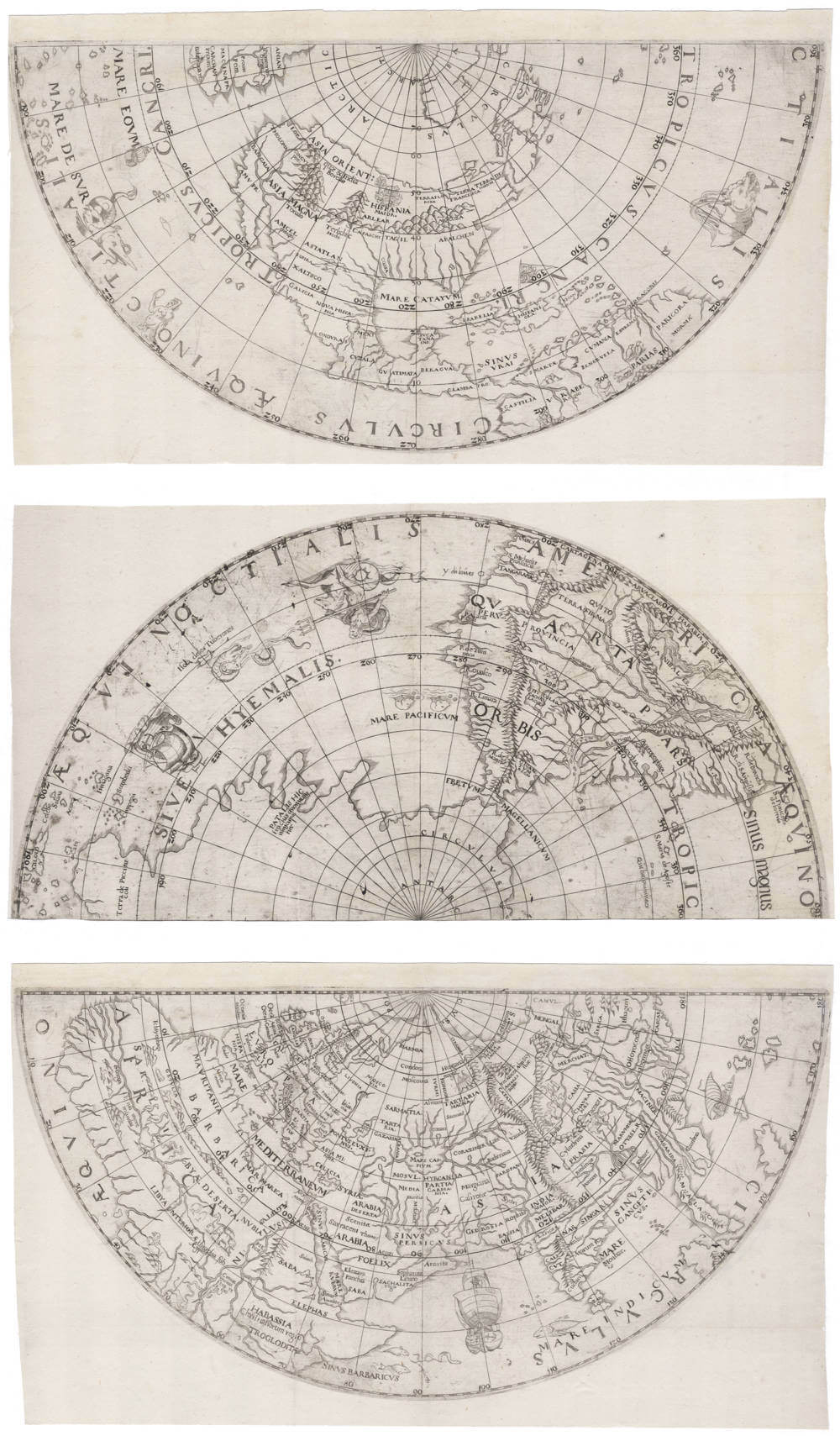

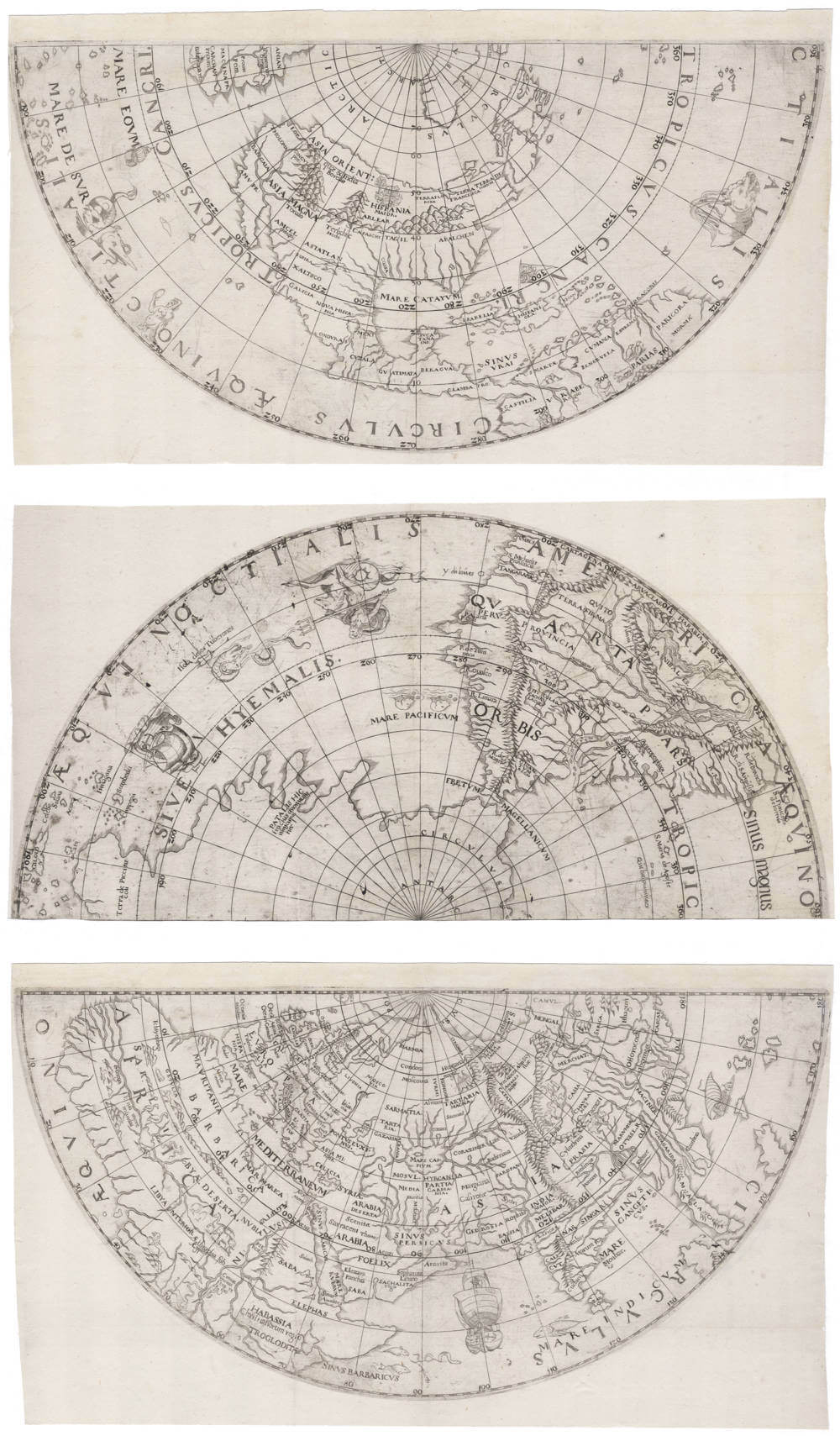

Unrecorded large copperplate map of the world, of utmost significance for the early history of the voyages of discovery.

Augsburg, 1564-1570, German School, anonymous, most likely by Georg Joachim Rheticus.

Printed from large demi-circular copperplates on separate sheets of paper.

Watermark Kaufbeuren, dating 1550-1570 (Briquet 914/915), from locally produced paper not found elsewhere, securely datable from contemporary archival sources.

The geographical content, toponyms and decorations reconciles two sources, that represented the old and the new gold standard of the day:

• Caspar Vopelius' wall map of the world of 1545 (now lost but surviving in a 1558 and 1570 derivative, Shirley 123)

• Abraham Ortelius' wall map of the world of 1564 (Shirley 114)

These were the most prestigious and influential wall maps of the world published north of the Alps, with copies on display in Augsburg in the (now lost) Fugger library.

As the present map incorporates content from Ortelius’ 1564 wall map, this provides the terminus post quem. The paper watermark, not found after 1570, fixes the terminus ante quem.

Important features and characteristics

• North America retains many Asian toponyms (ASIA ORIENT, LOP, ASIA MAGNA, INDIA BOREALIS, BANGAIA), combined with a few European names on the east coast (Terra Florida, Terra Francesca, Terra de Norvm).

• The Gulf of Mexico is labelled Mare Catayum (Sea of China), as in Vopelius’ map.

• The Spanish colours are flying over Hispaniola, as in Munster 1540.

• South America in an early cartography: Peru, Cusco, Lake Titicaca, the Orinoco and Amazon (under variant names), and the South Atlantic labelled Sinus Magnus.

• Japan is absent, though Cimpegu appears in the southern Pacific.

• Magellan’s circumnavigation (1519–22) is noted, including Isola de Tuberones (Shark Island, 1521, Kiribati).

• The Pacific bears multiple labels: MARE EOM (Eastern Sea), MARE DE SVR (Sea of the South), SIVE HYEMALIS (Wintry Sea), and MARE PACIFICUM (from Magellan).

• Terra Australis is depicted with the legendary region of Patalis, labelled PATALIS HIC tractus a nonnullis nuncupatur (“This region is called Patalis by some”).

• New Guinea is joined to the southern continent, labelled Terra de Piccinaecoli, as described in 1518 by Andrea Corsali, who first identified New Guinea and hypothesised that "its size makes it probable that it forms part of the southern continent (Continentis Australis)", thus hypothesizing the existence of Australia at a very early stage. On his voyage in 1516 from Lisbon to India, Corsali also was the first European to describe the Southern Cross (Crux).

• Among the earliest maps to use the double-hemisphere projection, predating Pastel 1582 (Shirley 144) and de Jode 1593 (Shirley 184).

• Decorations largely copied from Ortelius’ 1564 map.

Relation to Caspar Vopelius 1545 wall map of the world

The map retains most of Vopel’s lost 1545 wall map, then the cartographic standard. No examples of the wall map have survived, but a single example is known of a 1558 derivative by the Venetian cartographer Giovanni Vavassore, in Harvard (Shirley map 102), as well as one example of a 1570 version by van den Putte (Shirley 123).

Vopel aligned the discoveries of Columbus, da Gama, Magellan and Cortés, updating medieval and classical models. The present map preserves his Asian toponyms in North America. On his wall map, Caspar Vopel dedicates an extensive text legend to explain that he had joined New Spain with Asia because Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and of the Americas, had personally asserted him in a meeting with cartographers in Cologne, that, according to all reports that he received from there, his empire in America "adjoined the Oriental lands".

Relation to Abraham Ortelius 1564 wall map of the world

The map here is a direct response to Ortelius 1564 new wall map of the world (Shirley 114), which was a great success and widespread but has only survived in three copies (British Library, Maritime Museum Rotterdam, Basle University Library). While the world map here retains much of Vopel's 1545 map, it does adopt Ortelius' separation of America from Asia, which was one of the major cartographic mysteries for most of the 16th century, with foremost cartographers on both sides of the argument.

Relation to Jost Amman's 1564 map of the world

Some resemblance exists to the famous early miniature world map, only known in three examples (Greenwich, Vatican, Harvard), attributed to Jost Amman (Shirley map 113).

The Jost Amman map is also on double polar projection, of German origin and assumed to be published around the same date.

On geographical content, the Amman map of the world shows no connection to the map here, indicating that they are unrelated and developed independently.

However, Amman’s map differs entirely in content and sources. The present map is over twice the size, with distinct toponyms and decorations.

Attribution to Georg Joachim Rheticus

The fluent engraving, accurate toponyms and advanced projection point to a master cartographer. The double polar projection required complex trigonometry, precisely the expertise of Georg Joachim Rheticus, who had developed the necessary tables for exactly that.

As a pupil of Schöner and Copernicus, and an accomplished geographer, Rheticus would have known both Vopel’s 1545 and Ortelius’ 1564 wall maps. Reconciling and improving these models on a new projection fits naturally with his intellectual profile.

Significance

One of very few surviving world maps from he third quarter of the 16th century, distinct from any other from that crucial period.

The world map is of utmost significance to the early mapping of Asia, Australia, Pacific and the Americas.

In general, as with the other world maps of the day, the map maker aims to reconcile the sources from classical antiquity with the reports from Medieval travellers, with the discoveries from the Renaissance explorers.

In particular, in this case here the mapmaker tries to reconcile the two foremost authorities of world maps north of the Alps, combining Vopelius' established 1545 wall map of the world with the new Ortelius 1564 wall map of the world, by introducing new concepts to solve the great paradoxes of the day regarding the nature of the Americas, Asia and the Pacific, as reported by the great discoverers Columbus, Vasco da Gama, Magellan and Cortés.

Following the new Ortelius' wall map of the world of 1564, the mapmaker depicts the Americas as a separate continent, not an extension of Asia. On the other hand, the mapmaker retains Vopelius' East Asian toponyms for North America and the waters around it from his wall map of 1545 (including Mare Catayum, the sea of China), resulting in a unique map of the world unlike any other, setting a new cornerstone in the history of the early mapping of the world.

Rarity

Unrecorded item, the only copy known. Lacking in all collections.

Condition

Three sheets of originally four, lacking the half circle covering the southern hemisphere part with Africa and the western Indian Ocean. A crisp and even early imprint of the copperplates.

Georg Joachim Rheticus (1514-1574)

Early Life and Education

Georg Joachim Rheticus, born Georg Joachim von Lauchen, entered the world on February 16, 1514, in Feldkirch, in the Habsburg region of modern-day Austria. His father, Georg Iserin, was a physician and town doctor, but tragedy struck early: when Rheticus was just 14, his father was executed on charges of sorcery — an event that left a deep psychological and social scar on the young scholar. To avoid the social stigma, he adopted the name “Rheticus,” meaning “from Rhaetia,” the ancient Roman name for his Alpine homeland.

Rheticus’s early education took place in Feldkirch and Zürich. Around 1532, he entered the University of Wittenberg, a hotbed of Renaissance humanism and Protestant reform. There, he came under the wing of Philip Melanchthon, a leading figure of the Reformation, who nurtured Rheticus’s passion for mathematics, astronomy, and classical studies.

Another decisive influence in his intellectual development was Johannes Schöner (1477–1547), the famed Nuremberg astronomer, globe maker, mathematician, and geographer. Schöner, one of the leading instrument makers of the time, produced highly influential terrestrial and celestial globes and had access to the most cutting-edge geographic data, including Waldseemüller’s early world maps. As Schöner’s pupil, Rheticus absorbed advanced mathematical and cartographic knowledge and was introduced to the intersection of practical instrument-making and theoretical astronomy. This exposure deeply shaped his later contributions, particularly his blend of precise mathematical methods and geographical interests.

Meeting Copernicus and Launching the Heliocentric Revolution

In 1536, Rheticus was appointed professor of mathematics at Wittenberg, an extraordinary accomplishment for a man still in his early twenties. But his restless mind soon pushed him beyond the confines of the university. By the late 1530s, rumors circulated of a revolutionary thinker in distant Warmia (modern Poland) — Nicolaus Copernicus — who had developed a new model of the cosmos placing the Sun, not the Earth, at the center.

In 1539, Rheticus undertook a long and difficult journey to meet Copernicus in Frauenburg (Frombork). For more than two years, he worked side by side with the elder astronomer, absorbing the details of the heliocentric model and offering editorial and moral support. Recognizing the radical implications of Copernicus’s system, Rheticus became its first public advocate.

His Narratio Prima (“First Account”), published in 1540, was the first printed description of the Copernican heliocentric theory, and it caused a stir in European intellectual circles. Without Rheticus’s persistent encouragement and mediation, it is doubtful that Copernicus would have allowed his full manuscript, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, to see publication in 1543 — a work that would become one of the cornerstones of the Scientific Revolution.

Later Work: Maps, Mathematics, and Trigonometry

After his transformative period with Copernicus, Rheticus continued to navigate the shifting intellectual currents of Renaissance Europe. He returned to academic life but was increasingly drawn to applied mathematics, geography, and cartography — fields in which the influence of his earlier mentor Schöner remained evident.

Among his significant achievements was his role in the creation of the 1542 map of Prussia, one of the earliest systematic regional maps, produced in collaboration with Heinrich Zell. This project showcased Rheticus’s commitment to geographic precision and the practical application of mathematical surveying, echoing the instrument-making tradition he had inherited from Schöner.

Rheticus’s most enduring mathematical contribution was in the field of trigonometry. He was among the first European scholars to compile comprehensive tables of all six trigonometric functions — sine, cosine, tangent, cotangent, secant, and cosecant — extending them to unprecedented levels of precision. His life’s major work, the Opus Palatinum de Triangulis, was left incomplete at his death but was finalized and published by his student, Valentin Otho, in 1596. These tables became foundational tools for astronomers, geographers, and navigators in the late Renaissance.

Challenges, Exile, and Legacy

Despite his intellectual brilliance, Rheticus’s life was far from smooth. He became embroiled in personal scandals — notably accusations of homosexual conduct, a criminal charge in that era — and was forced into periods of exile and wandering. He worked in various cities, including Leipzig, Kraków, and Košice, shifting between academic posts and private commissions, often under the cloud of social and religious suspicion.

Rheticus died in December 1574 in Košice (present-day Slovakia), far from the bright centers of learning where he had once been a rising star. Yet despite his stormy personal life and occasional obscurity, his intellectual legacy remains profound.

Georg Joachim Rheticus occupies a unique and critical position in the history of science. As the first champion of the Copernican system, he bridged the gap between a reclusive Polish canon and a European audience ready — though often reluctant — to rethink the structure of the cosmos. His mathematical rigor, sharpened by his apprenticeship under Johannes Schöner, and his passion for geography and astronomy made him a versatile and brilliant figure of the Renaissance.

While no known world maps or globes authored by Rheticus survive, his contributions to regional mapping (notably the Prussian map) and his foundational trigonometric work had widespread influence. The intellectual daring he displayed — risking reputation and career to support Copernicus’s radical model — set the stage for later giants like Galileo, Kepler, and Newton.

Rheticus is thus remembered not only as a mathematician and astronomer but as a midwife of scientific revolution: the man who brought the Sun-centered universe into the public eye and transformed European science forever.

Caspar Vopelius (1511–1561)

Caspar Vopel, also known as Vopelius, Vopell, Vöpell, or Meydebachius, was a prominent 16th-century German cartographer, astronomer, mathematician, and instrument maker whose contributions to celestial and terrestrial cartography left a lasting impact on Renaissance geography. Born in 1511 in Medebach, a small town in the Sauerland region of Germany, Vopel’s life was marked by intellectual curiosity and innovative craftsmanship. His work, rooted in the mathematical and geographical studies of his time, bridged the gap between ancient astronomical traditions and the emerging scientific advancements of the Renaissance. Vopel’s globes, maps, and instruments, particularly his influential Map of the Rhine (1555), established him as a key figure in the cartographic history of Europe.

Early Life and Education

Vopel likely came from a respected and affluent family in Medebach, though little is known about his parents. A certain Hermann Vöpelen, documented as a judge and mayor of Medebach in 1530, may suggest a connection to local prominence. From an early age, Vopel displayed a keen interest in mathematics, which he pursued during his schooling in Medebach. In 1526, at the age of 15, he enrolled at the University of Cologne, a hub of intellectual activity. By November 1527, he earned the degree of Baccalaureus, and in March 1529, he achieved the titles of Licentiate and Magister Artium, demonstrating his rapid academic progress. His studies included mathematics and medicine, disciplines that would underpin his later cartographic and astronomical work.

Following his university education, Vopel joined the faculty of the Montaner-Gymnasium in Cologne, succeeding the Swiss humanist Henricus Glareanus as a mathematics teacher. This position not only solidified his reputation but also granted him Cologne citizenship, a significant achievement for a young scholar. Around this time, he married Enge van Aich, the daughter of the notable Cologne printer Arnt van Aich, and acquired a house in the Schildergasse from his father-in-law. Despite his wife’s family leaning toward the Reformation, Vopel remained loyal to the Catholic faith, navigating the religious tensions of the period by undertaking extended travels between 1545 and 1555. Whether children resulted from his marriage remains unknown.

Contributions to Cartography and Astronomy

Vopel’s career as a cartographer and instrument maker began in earnest in the early 1530s when he established a workshop in Cologne. His workshop produced a range of scientific instruments, including celestial and terrestrial globes, armillary spheres, sundials, quadrants, and astrolabes, which were highly valued for their precision and craftsmanship. His first major work, a hand-painted manuscript celestial globe created in 1532, is signed “Gaspar of Medebach” and is preserved in the Kölnisches Stadtmuseum. This globe, measuring 28 centimeters in diameter, featured the 1,025 fixed stars cataloged by Ptolemy in his Almagest, reflecting Vopel’s deep engagement with classical astronomy. In 1536, he produced a printed celestial globe, which introduced the constellations Coma Berenices and Antinous. While Coma Berenices was later recognized as a constellation, Antinous was reassigned to the constellation Aquila in 1928. These globes, preserved in Cologne and other collections, showcased Vopel’s innovative approach to celestial cartography, blending astronomical accuracy with mythological iconography inspired by humanist editions of Ptolemy’s star catalog.

In 1542, Vopel crafted a terrestrial globe that reflected the geographical knowledge of the time, including uncertainties about whether the lands discovered by Columbus were part of Asia. His armillary spheres, such as one preserved in Copenhagen, were designed for astrological and medical applications, indicating the interdisciplinary nature of his work. By 1545, Vopel expanded into mapmaking, producing a world map titled Nova et Integra Universalisque Orbis Totius Iuxta Germanam Neotericorum Traditionem Descriptio (A New Complete and Universal Description of the Whole World, According to the Modern German Tradition). This map, along with a 1555 map of Europe, demonstrated his ability to synthesize contemporary geographical data.

Vopel’s most celebrated work is his Map of the Rhine (1555), a monumental woodcut printed on three sheets, measuring 37.5 x 150 cm. Dedicated to the Cologne City Council, this hand-colored map depicted the Rhine River from its Swiss origins to its mouth in the Dutch North Sea with unprecedented detail. Oriented with west at the top, it included numerous place names, coats of arms, and annotations in German and Latin, as well as references to Roman-era tribes. Vopel drew on Swiss sources, such as Aegidius Tschudi and Johannes Stumpf, for the upper Rhine and Dutch sources for the river’s mouth, while the sources for the middle Rhine remain unknown. The map’s accuracy and aesthetic appeal made it a standard for Rhine cartography, influencing European mapmakers until the 18th century. Its popularity necessitated multiple editions, with a 1558 version dedicated to the Cologne Elector and a third edition in 1560. Twelve reprints are documented, and a facsimile was published in 1903 by geographer H. Michow. A preserved copy resides in the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel.

Legacy and Death

Vopel’s work extended beyond cartography into publishing and instrument design. From 1549, he published a writing manual by his colleague Caspar Neffe and developed brass cosmographic instruments, including compendiums combining quadrants, sundials, and aspectaria for astrological purposes. His globes and maps were widely copied, with his 1536 celestial globe influencing later works by Jacques de la Garde (1552), Jean Naze (1560), and others. His celestial maps, included in world maps by Valvassore (1558) and Van den Putte (1570), further spread his influence.

Vopel died in 1561 in Cologne, reportedly while preparing a comprehensive atlas of the world, a project that remained unfinished. His contributions earned him recognition in contemporary works, such as Mathias Quad’s Teutscher Nation Herligkeit (1609), which praised him as a “skillful and experienced geographer” from Medebach. Vopel’s legacy endures through his surviving globes, maps, and instruments, which are housed in institutions like the Kölnisches Stadtmuseum, Tenri University Library, and the Herzog August Bibliothek. His Map of the Rhine remains a testament to his ability to combine scientific precision with artistic expression, securing his place as a pioneer of 16th-century cartography.

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

Abraham Ortelius is the most famous and most collected of all early cartographers. In 1570 he published the first comprehensive collection of maps of all parts of the world, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum ("Theatre of the World"), the first modern atlas as we know it.

"Abraham Ortel, better known as Ortelius, was born in Antwerp and after studying Greek, Latin and mathematics set up business there with his sister, as a book dealer and ‘painter of maps'. Traveling widely, especially to the great book fairs, his business prospered and he established contacts with the literati in many lands. On one such visit to England, possibly seeking temporary refuge from religious persecution, he met William Camden whom he is said to have encouraged in the production of the Britannia.

A turning point in his career was reached in 1564 with the publication of a World Map in eight sheets of which only one copy is known: other individual maps followed and then – at the suggestion of a friend - he gathered together a collection of maps from contacts among European cartographers and had them engraved in uniform size and issued in 1570 as the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Atlas of the Whole World). Although Lafreri and others in Italy had published collections of ‘modern' maps in book form in earlier years, the Theatrum was the first uniformly sized, systematic collection of maps and hence can be called the first atlas, although that term itself was not used until twenty years later by Mercator.

The Theatrum, with most of its maps elegantly engraved by Frans Hogenberg, was an instant success and appeared in numerous editions in different languages including addenda issued from time to time incorporating the latest contemporary knowledge and discoveries. The final edition appeared in 1612. Unlike many of his contemporaries Ortelius noted his sources of information and in the first edition acknowledgement was made to eighty-seven different cartographers.

Apart from the modern maps in his major atlas, Ortelius himself compiled a series of historical maps known as the Parergon Theatri which appeared from 1579 onwards, sometimes as a separate publication and sometimes incorporated in the Theatrum."

(Moreland and Bannister)

"The maker of the ‘first atlas', the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570), started his career as a colorist of maps. Later, he became a seller of books, prints and maps. His scientific and collecting interests developed in harmony with those of a merchant. He was first and foremost a historian. Geography for him was the ‘eye of history', which may explain why, in addition to coins and historical objects, he also collected maps. On the basis of his extensive travels through Europe and with the help of his international circle of friends, Ortelius was able to build a collection of the most up-to-date maps available.

The unique position held by Ortelius's Theatrum in the history of cartography is to be attributed primarily to its qualification as ‘the world's first regularly produced atlas.' Its great commercial success enabled it to make a great contribution to ‘geographical culture' throughout Europe at the end of the sixteenth century. Shape and contents set the standard for later atlases, when the centre of the map trade moved from Antwerp to Amsterdam. The characteristic feature of the Theatrum is that it consists of two elements, text and maps. Another important aspect is that it was the first undertaking of its kind to reduce the best available maps to a uniform format. To that end, maps of various formats and styles had to be generalized just like the modern atlas publisher of today would do. In selecting maps for his compilation, Ortelius was guided by his critical spirit and his encyclopaedic knowledge of maps. But Ortelius did more than the present atlas makers: he mentioned the names of the authors of the original maps and added the names of many other cartographers and geographers to his list. This ‘catalogus auctorum tabularum geographicum,' printed in the Theatrum, is one of the major peculiarities of the atlas. Ortelius and his successors kept his list of map authors up-to-date. In the first edition of 1570 the list included 87 names. In the posthumous edition of 1603, it contained 183 names.

Abraham Ortelius himself drew all his maps in manuscript before passing them to the engravers. In the preface to the Theatrum he stated that all the plates were engraved by Frans Hogenberg, who probably was assisted by Ambrosius and Ferdinand Arsenius (= Aertsen). The first edition of the Theatrum is dated 20 May 1570 and includes 53 maps.

The Theatrum was printed at Ortelius's expense first by Gielis Coppens van Diest, an Antwerp printer who had experience with printing cosmographical works. From 1539 onwards, Van Diest had printed various editions of Apianus's Cosmographia, edited by Gemma Frisius, and in 1552 he printed Honterus's Rudimentorum Cosmograhicorum... Libri IIII. Gielis Coppens van Diest was succeeded as printer of the Theatrum in 1573 by his son Anthonis, who in turn was followed by Gillis van den Rade, who printed the 1575 edition. From 1579 onwards Christoffel Plantin printed the Theatrum, still at Ortelius's own expense. Plantin and later his successors continued printing the work until Ortelius's heirs sold the copperplates and the publication rights in 1601 to Jan Baptist Vrients, who added some new maps. After 1612, the year of Vrients's death, the copperplates passed to the Moretus brothers, the successors of Christoffel Plantin.

The editions of the Theatrum may be subdivided into five groups on the basis of the number of maps. The first group contains 53 maps, 18 maps were added. The second group has 70 maps (one of the 18 new maps replaced a previous one). In 1579 another expansion was issued with 23 maps. Some maps replaced older ones, so as of that date the Theatrum contained 112. In 1590 a fourth addition followed with 22 maps. The editions then had 134 maps. A final, fifth expansion with 17 maps followed in 1595, bringing the total to 151."

(Peter van der Krogt, Atlantes Neerlandici New Edition, Volume III)