Leen Helmink Antique Maps & Atlases

www.helmink.com

Valentijn

Anthony van Diemens Land

Certificate of Authentication and Description

This is to certify that the item illustrated and described below is a genuine antique

map, print or book that was first produced and published in 1726, today 300 years ago.

February 17, 2026

Cartographer(s)

Valentijn

First Published

Amsterdam, 1726

This edition

1726

Size

cms

Technique

Copper engraving

Stock number

19055

Condition

pristine

Description

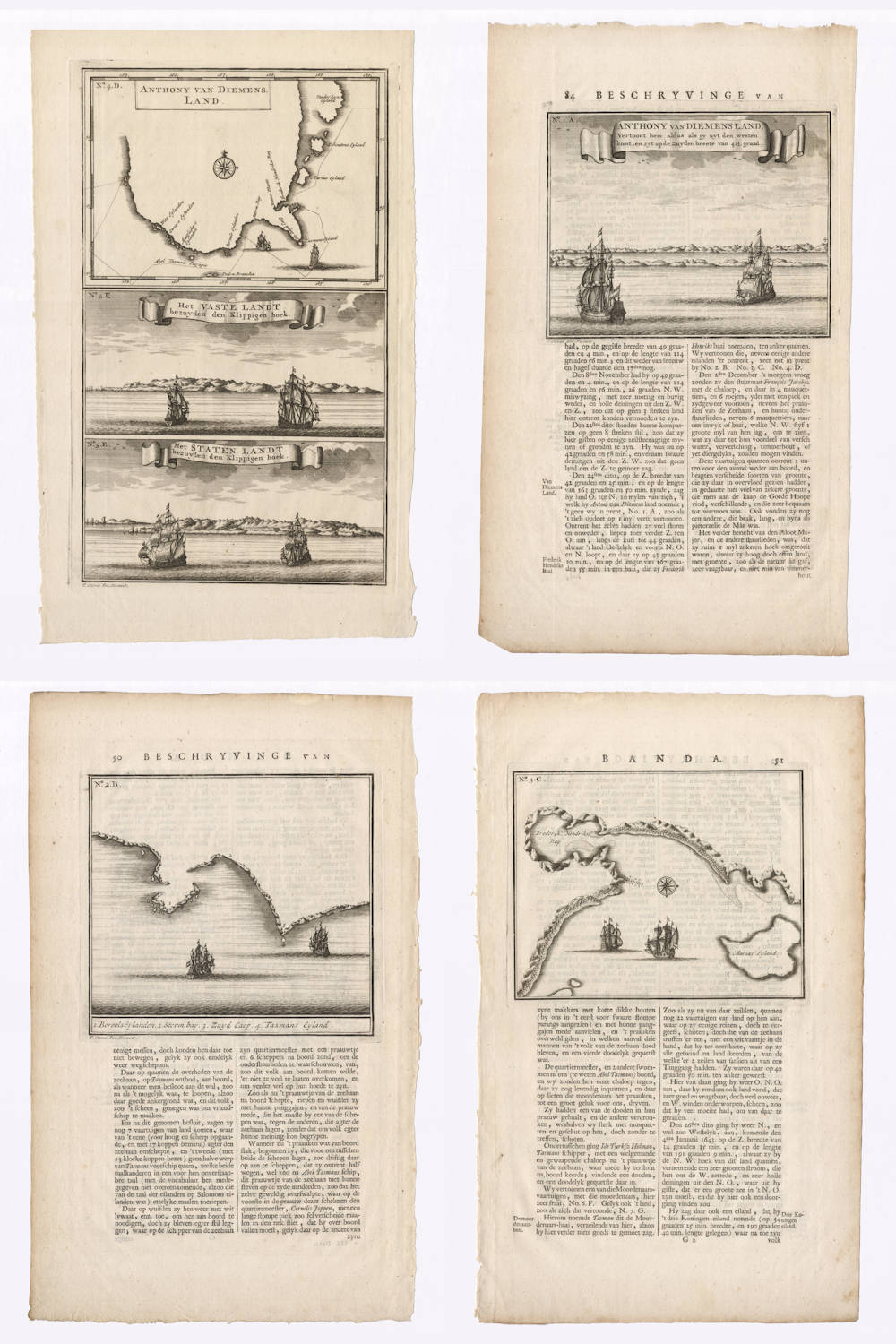

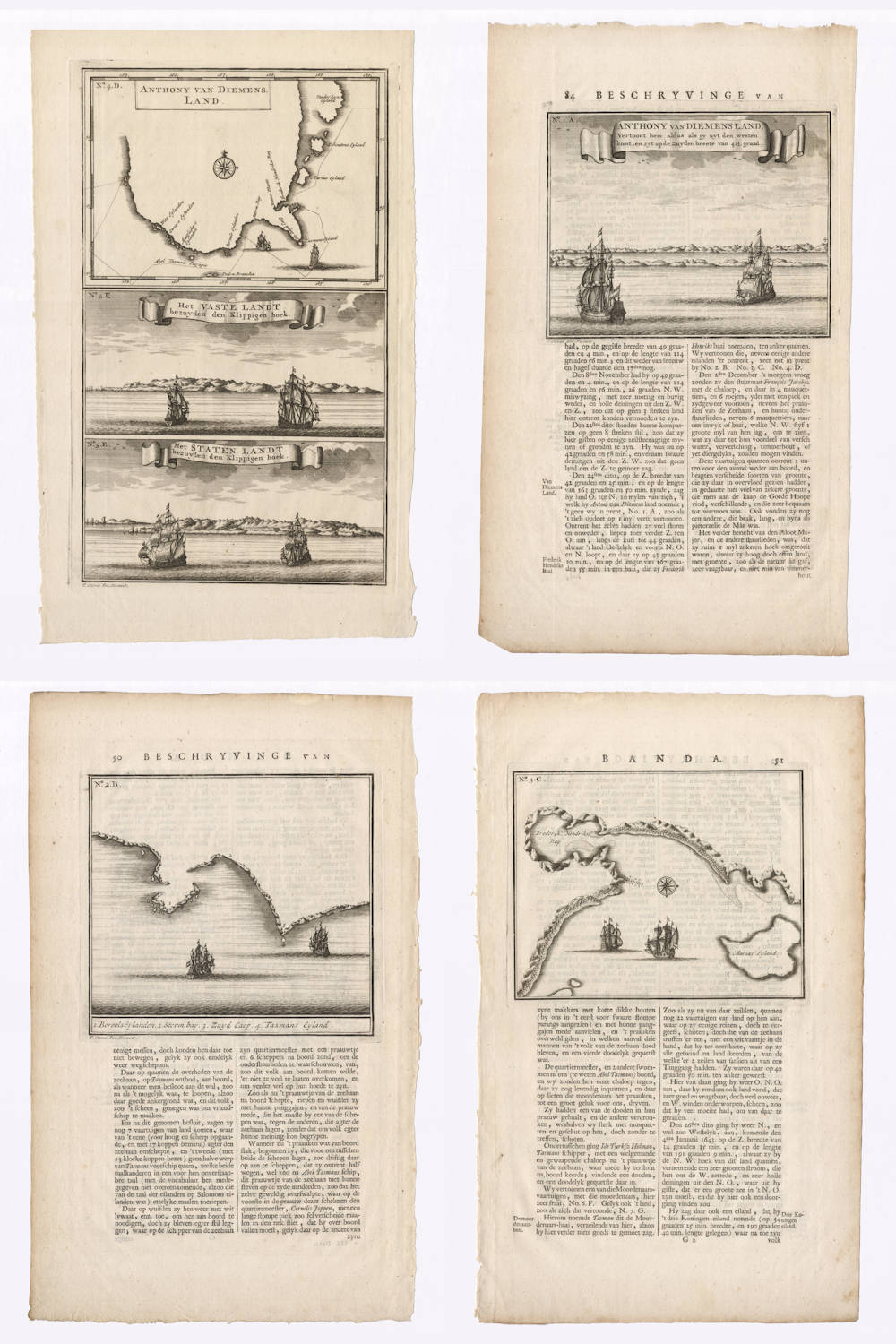

Valentijn's four copper engravings of Tasman's 1642 discovery of Tasmania.

Condition

Strong and early imprints of the copperplates. Good paper margins. Mint collector's condition.

Source

Valentijn has copied the charts, coastal profiles and legends from Abel Tasman's journal, now in the Dutch National Archives. The journal is reproduced online here by the National Library of Australia.

Below are the entries on the discovery of Tasmania from the English translation of Tasman's original journal by J.E. Heeres, published in 1898.

ABEL JANSZOON TASMAN'S JOURNAL in the The Hague Archives

[November 1642]

Item the 24th [of November].

Good weather and a clear sky. At noon Latitude observed 42° 25', Longitude 163° 31'; course kept east by north, sailed 30 miles; the wind south-westerly and afterwards from the south with a light top-gallant breeze. In the afternoon about 4 o'clock we saw land bearing east by north of us at about 10 miles distance from us by estimation; the land we sighted was very high; towards evening we also saw, east-south-east of us, three high mountains, and to the north-east two more mountains, but less high than those to southward; we found that here our compass pointed due north. In the evening in the first glass after the watch had been set, we convened our ship's council with the second mate's and represented to them whether it would not be advisable to run farther out to sea; we also asked their advice as to the time when it would be best to do so, upon which it was unanimously resolved to run out to sea at the expiration of three glasses, to keep doing so for the space of ten glasses, and after this to make for the land again; all of which may in extenso be seen from today's resolution to which we beg leave to refer. During the night when three glasses had run out the wind turned to the south-east; we held off from shore and sounded in 100 fathom, fine white sandy bottom with small shells; we sounded once more and found black coarse sand with pebbles; during the night we had a south-east wind with a light breeze.

Item the 25th.

In the morning we had a calm; we floated the white flag and pendant from our stern, upon which the officers of the Zeehaan with their steersmen came on board of us; we then convened the Ship's council and resolved together upon what may in extenso be seen from today's resolution to which we beg leave to refer. Towards noon the wind turned to the south-east and afterwards to the south-south-east and the south, upon which we made for the shore; at about 5 o'clock in the evening we got near the coast; three miles off shore we sounded in 60 fathom coral bottom; one mile off the coast we had clean, fine, white sand; we found this coast to bear south by east and north by west; it was a level coast, our ship being 42° 30' South Latitude, and average Longitude 163° 50'. We then put off from shore again, the wind turning to the south-south-east with a top-gallant gale. If you came from the west and find your needle to show 4° north-westerly variation you had better look out for land, seeing that the variation is very abruptly decreasing here. If you should happen to be overtaken by rough weather from the westward you had best heave to and not run on. Near the coast here the needle points due north. We took the average of our several longitudes and found this land to be in 163° 50' Longitude.

This land being the first land we have met with in the South Sea and not known to any European nation we have conferred on it the name of Anthoony Van Diemenslandt in honour of the Honourable Governor-General, our illustrious master, who sent us to make this discovery; the islands circumjacent, so far as known to us, we have named after the Honourable Councillors of India, as may be seen from the little chart which has been made of them.

Item the 26th.

We had the wind from eastward with a light breeze and hazy weather so that we could see no land; according to our estimation we were at 9½ miles distance from shore. Towards noon we hoisted the top-pendant upon which the Zeehaan forthwith came astern of us; we called out to her men that we should like Mr. Gilsemans to come on board of us, upon which the said Mr. Gilsemans straightways came on board of us, to whom we imparted the reasons set forth in the subjoined letter which we enjoined him to take with him on board the Zeehaan, to be shown to Skipper Gerrit Jansz, who is to give orders to her steersmen in accordance with its purport:

The officers of the Flute Zeehaan are hereby enjoined to set down

in their daily journals this land which we saw and came near to

yesterday in the longitude of 163° 50', seeing that we have found

this to be its average longitude, and to lay down the said longitude

as an established point of departure for their further reckonings; he

who before this had got the longitude of 160° or more will

henceforth have to take this land for his starting-point; we make the

arrangement in order to preclude all errors as much as is at all

possible. The officers of the Zeehaan are requested to give orders in

conformity to her steersmen and to see them acted up to, because we

opine this to be their duty; any charts that should be drawn up of

this part will have to lay down this land in the average longitude of

163° 50' as hereinbefore stated.

Actum Heemskerk datum ut supra

(signed) ABEL JANSZ. TASMAN.

At noon Latitude estimated 43° 36' South, Longitude 163° 2'; course kept south-south-west, sailed 18 miles. We had ½ degree North-West variation; in the evening the wind went round to the north-east, and we changed our course to east-south-east.

Item the 27th.

In the morning we again saw the coast, our course still being east-south-east. At noon Latitude estimated 44° 4' South, Longitude 164° 2'; course kept south-east by east, sailed 13 miles; the weather was drizzly, foggy, hazy and rainy, the wind north-east and north-north-east with a light breeze; at night when 7 glasses of the first watch had run out we began trying under reduced sail because we dared not run on owing to thick darkness.

Item the 28th.

In the morning, the weather still being dark, foggy and rainy, we again made sail, shaped our course to eastward and afterwards north-east by north; we saw land north-east and north-north-east of us and made straight for it; the coast here bears south-east by east and north-west by west; as far as I can see the land here falls off to eastward. At noon Latitude estimated 44° 12', Longitude 165° 2'; course kept west by south, sailed 11 miles with a north-westerly wind and a light breeze. In the evening we got near the coast; here near the shore there are a number of islets of which one in shape resembles a lion; this islet lies out into the sea at about 3 miles distance from the mainland; in the evening the wind turned to the east; during the night we lay a-trying under reduced sail.

Item the 29th.

In the morning we were still near the rock which is like a lion's head; we had a westerly wind with a top-gallant gale; we sailed along the coast which here bears east and west; towards noon we passed two rocks of which the westernmost was like Pedra Branca off the coast of China; the easternmost was like a tall, obtuse, square tower, and is at about 4 miles distance from the mainland. We passed between these rocks and the mainland; at noon Latitude estimated 43° 53', Longitude 166° 3'; course kept east-north-east, sailed 12 miles; we were still running along the coast. In the evening about 5 o'clock we came before a bay which seemed likely to afford a good anchorage, upon which we resolved with our ship's council to run into it, as may be seen from today's resolution; we had nearly got into the bay when there arose so strong a gale that we were obliged to take in sail and to run out to sea again under reduced sail, seeing that it was impossible to come to anchor in such a storm; in the evening we resolved to stand out to sea during the night under reduced sail to avoid being thrown on a lee-shore by the violence of the wind; all which may in extenso be seen from the resolution aforesaid to which for briefness sake we beg to refer.

Item the last.

At daybreak we again made for shore, the wind and the current having driven us so far out to sea that we could barely see the land; we did our utmost to get near it again and at noon had the land north-west of us; we now turned the ship's head to westward with a northerly wind which prevented us from getting close to the land. At noon Latitude observed 43° 41', Longitude 168° 3'; course kept east by north, sailed 20 miles in a storm and with variable weather. The needle points due north here. Shortly after noon we turned our course to westward with a strong variable gale; we then turned to the north under reduced sail.

[December 1642]

Item the 1st of December.

In the morning, the weather having become somewhat better, we set our topsails, the wind blowing from the west-south-west with a top-gallant gale; we now made for the coast. At noon Latitude observed 43° 10', Longitude 167° 55'; course kept north-north-west, sailed 8 miles, it having fallen a calm; in the afternoon we hoisted the white flag upon which our friends of the Zeehaan came on board of us, with whom we resolved that it would be best and most expedient, wind and weather permitting, to touch at the land the sooner the better, both to get better acquainted with its condition and to attempt to procure refreshments for our own behoof, all which may be more amply seen from this day's resolution. We then got a breeze from eastward and made for the coast to ascertain whether it would afford a fitting anchorage; about one hour after sunset we dropped anchor in a good harbour, in 22 fathom, white and grey fine sand, a naturally drying bottom; for all which it behoves us to thank God Almighty with grateful hearts.

[The 8 pages following contain coast-surveyings and charts with inscriptions]

Item the 2nd.

Early in the morning we sent our Pilot-major Francoys Jacobsz in command of our pinnace, manned with 4 musketeers and 6 rowers, all of them furnished with pikes and side-arms, together with the cock-boat of the Zeehaan with one of her second mates and 6 musketeers in it, to a bay situated north-west of us at upwards of a mile distance in order to ascertain what facilities (as regards fresh water, refreshments, timber and the like) may be available there. About three hours before nightfall the boats came back, bringing various samples of vegetables which they had seen growing there in great abundance, some of them in appearance not unlike a certain plant growing at the Cape of Good Hope and fit to be used as pot-herbs, and another species with long leaves and a brackish taste, strongly resembling persil de mer or samphire. The Pilot-major and the second mate of the Zeehaan made the following report, to wit:

That they had rowed the space of upwards of a mile round the said point, where they had found high but level land covered with vegetation (not cultivated, but growing naturally by the will of God) abundance of excellent timber, and a gently sloping watercourse in a barren valley, the said water, though of good quality, being difficult to procure because the watercourse was so shallow that the water could be dipped with bowls only.

That they had heard certain human sounds and also sounds nearly resembling the music of a trump or a small gong not far from them though they had seen no one.

That they had seen two trees about 2 or 2½ fathom in thickness measuring from 60 to 65 feet from the ground to the lowermost branches, which trees bore notches made with flint implements, the bark having been removed for the purpose; these notches, forming a kind of steps to enable persons to get up the trees and rob the birds' nests in their tops, were fully 5 feet apart so that our men concluded that the natives here must be of very tall stature, or must be in possession of some sort of artifice for getting up the said trees; in one of the trees these notched steps were so fresh and new that they seemed to have been cut less than four days ago.

That on the ground they had observed certain footprints of animals, not unlike those of a tiger's claws; they also brought on board certain specimens of animals excrements voided by quadrupeds, so far as they could surmise and observe, together with a small quantity of gum of a seemingly very fine quality which had exuded from trees and bore some resemblance to gum-lac.

That round the eastern point of this bay they had sounded 13 or 14 feet at high water, there being about 3 feet at low tide.

That at the extremity of the said point they had seen large numbers of gulls, wild ducks and geese, but had perceived none farther inward though they had heard their cries; and had found no fish except different kinds of mussels forming small clusters in several places.

That the land is pretty generally covered with trees standing so far apart that they allow a passage everywhere and a lookout to a great distance so that, when landing, our men could always get sight of natives or wild beasts, unhindered by dense shrubbery or underwood, which would prove a great advantage in exploring the country.

That in the interior they had in several places observed numerous trees which had deep holes burnt into them at the upper end of the foot, while the earth had here and there been dug out with the fist so as to form a fireplace, the surrounding soil having become as hard as flint through the action of the fire.

A short time before we got sight of our boats returning to the ships, we now and then saw clouds of dense smoke rising up from the land, which was nearly west by north of us, and surmised this might be a signal given by our men, because they were so long coming back, for we had ordered them to return speedily, partly in order to be made acquainted with what they had seen, and partly that we might be able to send them to other points if they should find no profit there, to the end that no precious time might be wasted. When our men had come on board again we inquired of them whether they had been there and made a fire, to which they returned a negative answer, adding however that at various times and points in the wood they also had seen clouds of smoke ascending. So there can be no doubt there must be men here of extraordinary stature. This day we had variable winds from the eastward, but for the greater part of the day a stiff, steady breeze from the south-east.

Item the 3rd.

We went to the south-east side of this bay in the same boats as yesterday with Supercargo Gilsemans and a number of musketeers, the oarsmen furnished with pikes and side-arms; here we found water, it is true, but the land is so low-lying that the fresh water was made salt and brackish by the surf, while the soil is too rocky to allow of wells being dug; we therefore returned on board and convened the councils of our two ships with which we have resolved and determined what is set forth in extenso in today's resolution, to which for briefness sake we refer. In the afternoon we went to the south-east side of this bay in the boats aforesaid, having with us Pilot-major Francoys Jacobsz, Skipper Gerrit Jansz, Isack Gilsemans, supercargo on board the Zeehaan, subcargo Abraham Coomans, and our master carpenter Pieter Jacobsz; we carried with us a pole with the Company's mark carved into it, and a Prince-flag to be set up there, that those who shall come after us may become aware that we have been here, and have taken possession of the said land as our lawful property. When we had rowed about halfway with our boats it began to blow very stiffly, and the sea ran so high that the cock-boat of the Zeehaan, in which were seated the Pilot-major and Mr. Gilsemans, was compelled to pull back to the ships, while we ran on with our pinnace. When we had come close inshore in a small inlet which bore west-south-west of the ships the surf ran so high that we could not get near the shore without running the risk of having our pinnace dashed to pieces. We then ordered the carpenter aforesaid to swim to the shore alone with the pole and the flag, and kept by the wind with our pinnace; we made him plant the said pole with the flag at top into the earth, about the centre of the bay near four tall trees easily recognisable and standing in the form of a crescent, exactly before the one standing lowest. This tree is burnt in just above the ground, and in reality taller than the other three, but it seems to be shorter because it stands lower on the sloping ground; at top, projecting from the crown, it shows two long dry branches, so symmetrically set with dry sprigs and twigs that they look like the large antlers of a stag; by the side of these dry branches, slightly lower down, there is another bough which is quite green and leaved all round, whose twigs, owing to their regular proportion, wonderfully embellish the said bough and make it look like the upper part of a larding-pin. Our master carpenter, having in the sight of myself, Abel Jansz Tasman, Skipper Gerrit Jansz, and Subcargo Abraham Coomans, performed the work entrusted to him, we pulled with our pinnace as near the shore as we ventured to do; the carpenter aforesaid thereupon swam back to the pinnace through the surf. This work having been duly executed we pulled back to the ships, leaving the above-mentioned as a memorial for those who shall come after us, and for the natives of this country, who did not show themselves, though we suspect some of them were at no great distance and closely watching our proceedings. We made no arrangements for gathering vegetables since the high seas prevented our men from getting ashore except by swimming, so that it was impossible to get anything into the pinnace. During the whole of the day the wind blew chiefly from the north; in the evening we took the sun's azimuth and found 3° north-easterly variation of the compass; at sunset we got a strong gale from the north which by and by rose to so violent a storm from the north-north-west that we were compelled to get both our yards in and drop our small bower-anchor.

Item the 4th.

At dawn the storm abated, the weather became less rough and, the land-wind blowing from the west by north, we hove our bower-anchor; when we had weighed the said anchor and got it above the water we found that both the flukes were broken off so far that we hauled home nothing but the shank; we then weighed the other anchor also and set sail forthwith in order to pass to north to landward of the northernmost islands and seek a better watering-place. Here we lay at anchor in 43° South Latitude, Longitude 167½°; in the forenoon the wind was westerly. At noon Latitude observed 42° 40', Longitude 168°, course kept north-east, sailed 8 miles; in the afternoon the wind turned to the north-west; we had very variable winds all day; in the evening the wind went round to west-north-west again with a strong gale, then to west by north and west-north-west again with a strong gale, then to west by north and west-north-west once more; we then tacked to northward and in the evening saw a round mountain bearing north-north-west of us at about 8 miles distance; course kept to northward very close to the wind. While sailing out of this bay and all through the day we saw several columns of smoke ascend along the coast. Here it would be meet to describe the trend of the coast and the islands lying off it but we request to be excused for briefness sake and beg leave to refer to the small chart drawn up of it which we have appended.

Item the 5th.

In the morning, the wind blowing from the north-west by west, we kept our previous course; the high round mountain which we had seen the day before now bore due west of us at 6 miles distance; at this point the land fell off to the north-west so that we could no longer steer near the coast here, seeing that the wind was almost ahead. We therefore convened the council and the second mates, with whom after due deliberation we resolved, and subsequently called out to the officers of the Zeehaan that, pursuant to the resolution of the 11th ultimo we should direct our course due east, and on the said course run on to the full longitude of 195° or the Salomonis islands, all which will be found set forth in extenso in this day's resolution. At noon Latitude estimated 41° 34', Longitude 169°, course kept north-east by north, sailed 20 miles; we then shaped our course due east for the purpose of making further discoveries and of avoiding the variable winds between the trade-wind and the anti-trade-wind; the wind from the north-west with a steady breeze; during the night the wind from the west, a brisk steady breeze and good clear weather.

J.E. Heeres' translation.

François Valentijn (1666 – 1727)

François Valentijn (17 April 1666 – 1727) was a Dutch minister, naturalist and author whose Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën ("Old and New East-Indies") describes the history of the Dutch East India Company and the countries of the Far East.

François Valentijn was born in 1666 in Dordrecht, as the eldest of seven children of Abraham Valentijn and Maria Rijsbergen. He lived most of his life in Dordrecht; however, he is known for his activities in the tropics, notably in Ambon, in the Maluku Archipelago. Valentijn studied theology and philosophy at the University of Leiden and the University of Utrecht before leaving for a career as a preacher in the Indies.

In total, Valentijn lived in the East Indies for 16 years. Valentijn was first employed by the VOC (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie) at the age of 19 as minister to the East Indies, where he became a friend of the German naturalist Georg Eberhard Rumpf (Rumphius). He returned and lived in the Netherlands for about ten years before returning to the Indies in 1705 where he was to serve as army chaplain on an expedition in eastern Java.

He finally returned to Dordrecht where he found time to write his Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën (1724–26) a massive work of five parts published in eight volumes and containing over one thousand engraved illustrations and some of the most accurate maps of the Indies of the time. He died in The Hague, Netherlands, in 1727.

Valentijn probably had access to the VOC's archive of maps and geographic trade secrets, which they had always guarded jealously. Johannes van Keulen II (d. 1755) became Hydrographer to the V.O.C. at the time Valentijn's Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën was published. It was in the younger van Keulen's time that many of the VOC charts were first published, one signal of the decline of Dutch dominance in the spice trade. One uncommon grace afforded Valentijn was that he lived to see his work published; the VOC (Dutch East India Company) strictly enforced a policy prohibiting former employees from publishing anything about the region or their colonial administration.

(Wikipedia)

"The first book to give a comprehensive account, in text and illustration, of the peoples, places and natural history of Indonesia."

(Bastin & Brommer)

The Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien was created both from the voluminous journals Valentijn had amassed during his two stays in Southeast Asia, as well as from his own research, correspondence, and from previously unpublished material secured from VOC officials. The work contained an unprecedented selection of large-scale maps and views of the Indies, many of which were superior to previously available maps.

(Suarez)

François Valentijn's Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien (Old and New East Indies) has for long been regarded as a primary source of information on a number of regions of maritime Asia. It is a veritable encyclopaedia, bringing together an array of facts, trivial and vital, from a wide range of contemporary and earlier literature, acknowledged and unacknowledged, and contains valuable excerpts from contemporary documents of the Dutch East India Company and from private papers.

(Arasaratnam)

The most extensive geographical and historical description of the whole area the Dutch V.O.C. had taken into possession or had gained a foothold in: the East Indies, parts of China, Japan, parts of the Near East, and the Cape of Good Hope. This work still is the main source for the early history of the East Indies, especially for Ambon, where the author lived for years, as well as for the Moluccas, Ceylon, Japan, China, the Cape of Good Hope, etc. The work presents many documents which now are lost, and contains interesting statistics on the products and the trade in the various countries. It also contains the accounts of two early voyages to Australia, with interesting maps. And last but not least, the work also is of great interest today for its rich and beautiful illustrations, its early maps and views, engraved by the best Dutch artists of the time, such as F. Ottens, J.C. Philips, J. Goeree, G. Schoute and J. Lamsvelt etc., mostly after designs by M. Balen.

(Hesselink)

François Valentijn was born on April 17, 1666, in the city of Dordrecht, the Netherlands, as the eldest of seven children of Abraham Valentijn and Maria Rijsbergen. He studied theology at the universities of Utrecht and Leiden. During his life he spent nearly fifteen years as a minister in the Dutch East-Indies (1685–1694 and 1706–1713), mostly in the Moluccan Archipelago. In 1692 he entered into matrimony with Cornelia Snaats (1660–1717) who bore him two daughters. Valentijn died on August 6, 1727, in the city of The Hague. Valentijn is often noted for his role in discussions about early translations of the Bible into Malay. However, his established reputation rests on his multivolume work on Asia titled Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indië (Old and New East-Indies).

REVEREND VALENTIJN IN THE MOLUCCAS

At the age of nineteen, Valentijn was called to the ministry on Ambon Island, the chief trade and administrative hub of the Moluccan Archipelago. In the city of Ambon, he preached in the Malay language and trained local Ambonese assistant ministers, while also having to inspect some fifty Christian parishes in the region.

In the 1600s the catechism and liturgy were offered in so-called High-Malay, which most local Christians did not understand. Valentijn fervently opposed the use of High-Malay and instead propagated Ambon-Malay because, in his opinion, all Christian communities in the Indies understood this local dialect.

During his stay in Ambon, a number of Valentijn's colleagues blamed him for paying too much attention to his wife and making a living from usury. On top of these accusations, he was found guilty of manipulating official church records. The relationship with his colleagues grew tense because Valentijn disliked his task of inspecting the Christian parishes on other islands. In 1694 he returned to the Netherlands where he spent much time on his Bible translation.

In 1705 Valentijn returned to Ambon. During this period, Reverend Valentijn got into a conflict with the governor of Ambon about too much interference of the secular administration in church affairs without the consent of the church administration. This conflict worsened after Valentijn rejected his call by the central colonial administration to the island of Ternate. In 1713 his repeated request for repatriation was finally met.

THE MALAY BIBLE TRANSLATION

In 1693 during a meeting with the Church Council of Batavia, Valentijn announced that he had completed the translation of the Bible into Ambon-Malay. The Church Council refused to publish Valentijn's translation because two years earlier they assigned the task of translating the Bible into High-Malay to the Batavia-based Reverend Melchior Leydecker.

After Valentijn returned to the Netherlands in 1695, he rallied support for his translation. A heated discussion unfolded, in which Valentijn and, amongst others, the Dutch Reformed synods of both the provinces of North- and South-Holland, opposed the critique of Leydecker and the Church Council of Batavia. The Council's criticism largely concerned Valentijn's use of a poor dialect of Malay. The synods in the Netherlands were not in the position to participate in the debate as most relevant linguists resided in the Indies, but Valentijn's personal network most likely contributed to the support for Valentijn's translation.

In 1706 a special commission of ministers in the Indies inspected a revised edition of Valentijn's translation but still noticed a number of shortcomings. Although Valentijn told the commission that he would redo the translation, the final revised edition was never presented to the Church Council. The Council eventually decided to publish Leydecker's High-Malay translation, which was used in the Moluccas from 1733 onward into the twentieth century.

OUD EN NIEUW OOST-INDIË

From 1719 onward, Valentijn, as a private citizen, devoted himself chiefly to his magnum opus, Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indië (ONOI), comprising his own notes, observations, sections of writings from his personal library, and materials trusted to him by former colonial officials. In 1724, the first two volumes were published in the cities of Dordrecht and Amsterdam, followed by the following three volumes in 1726. This work comprises geographical and ethnological descriptions of the Moluccas and the trading contacts of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) throughout Asia.

Scholars consider this substantial work the first Dutch encyclopedic reference for Asia. ONOI contains factual data, descriptions of persons and towns, anecdotes, ethnological engravings, maps, sketches of coastlines, and city plans, as well as excerpts of official documents of the church council and colonial administration.

Valentijn wrote in an uncorrupted form of Dutch, which many contemporary writers were not able to compete with. The structure of Valentijn's colossal work is rather chaotic: the descriptions of more than thirty regions are erratically spread over a total number of forty-nine books in five volumes, each consisting of two parts, and held together in eight bindings.

Since the publication of ONOI, numerous scholars have accused Valentijn of plagiarism. It is true that he included abstracts of other works, such as the celebrated account on the Ambon islands by Rumphius, without referencing them properly. However, general acknowledgment of sources can be found in several places, for example, in his preface to the third volume.

THE INFLUENCE OF VALENTIJN'S WORK

For almost two centuries, Valentijn's work was the single credible reference for Asia. ONOI was therefore used as the main manual for Dutch civil servants and colonial administrators who were sent to work in the East Indies.

Valentijn's work is still a major source for historical studies on the Dutch East Indies. For example, the reference book on Dutch-Asiatic shipping in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (The Hague, 1979–1987) was compiled on the basis of materials derived from Valentijn's work. The importance of ONOI for the historical reconstruction of other regions is clearly demonstrated by the publication of English translations of Valentijn's parts concerning the Cape of Good Hope (1971–1973) and the first twelve chapters of his description of Ceylon (1978).

Valentijn's work also proved to be of great importance for the natural history of the Moluccas. Valentijn included in ONOI descriptions by Rumphius on, for example, Ambonese animals, while Rumphius's original unpublished manuscript was later lost. In 1754 Valentijn's part on sea flora and fauna was separately published in Amsterdam, and some twenty years later translated into German. It was only in 2004 that the complete ONOI was reprinted and made available to a larger public.

(Encyclopedia.com)