Leen Helmink Antique Maps & Atlases

www.helmink.com

de Jode

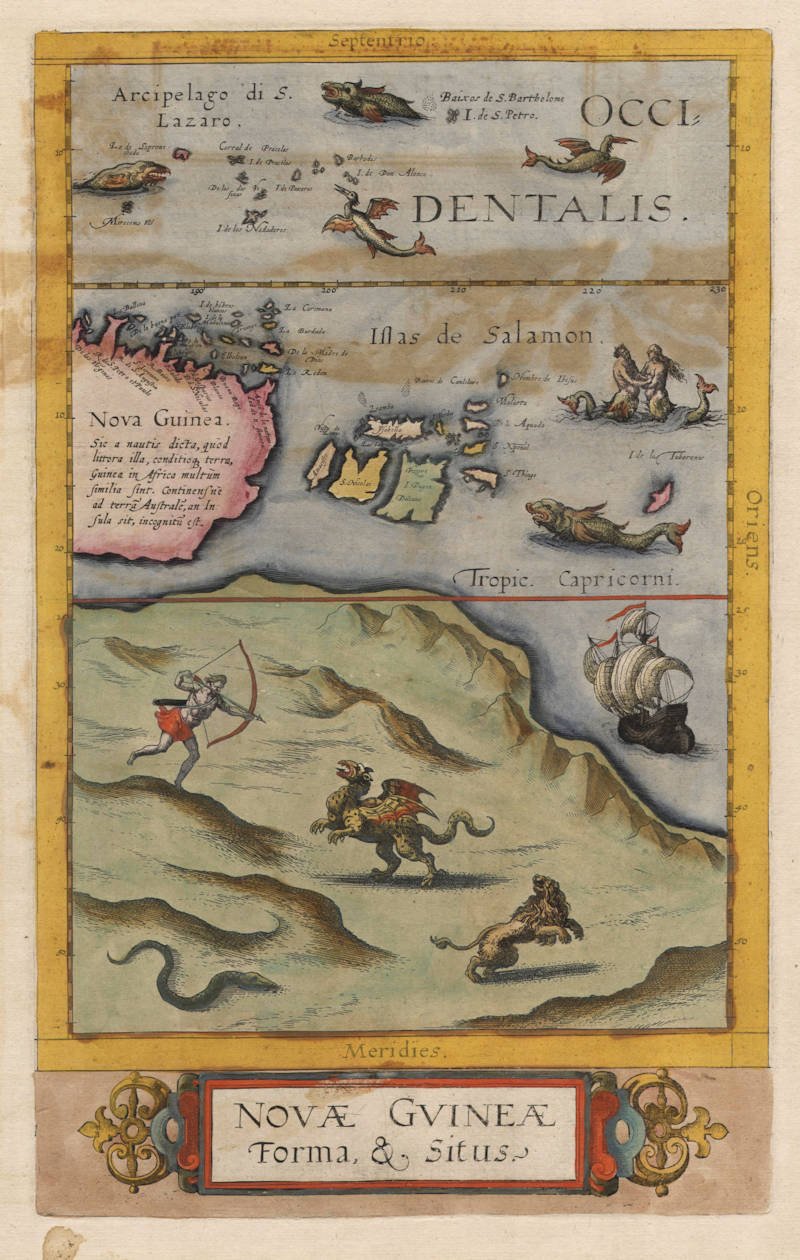

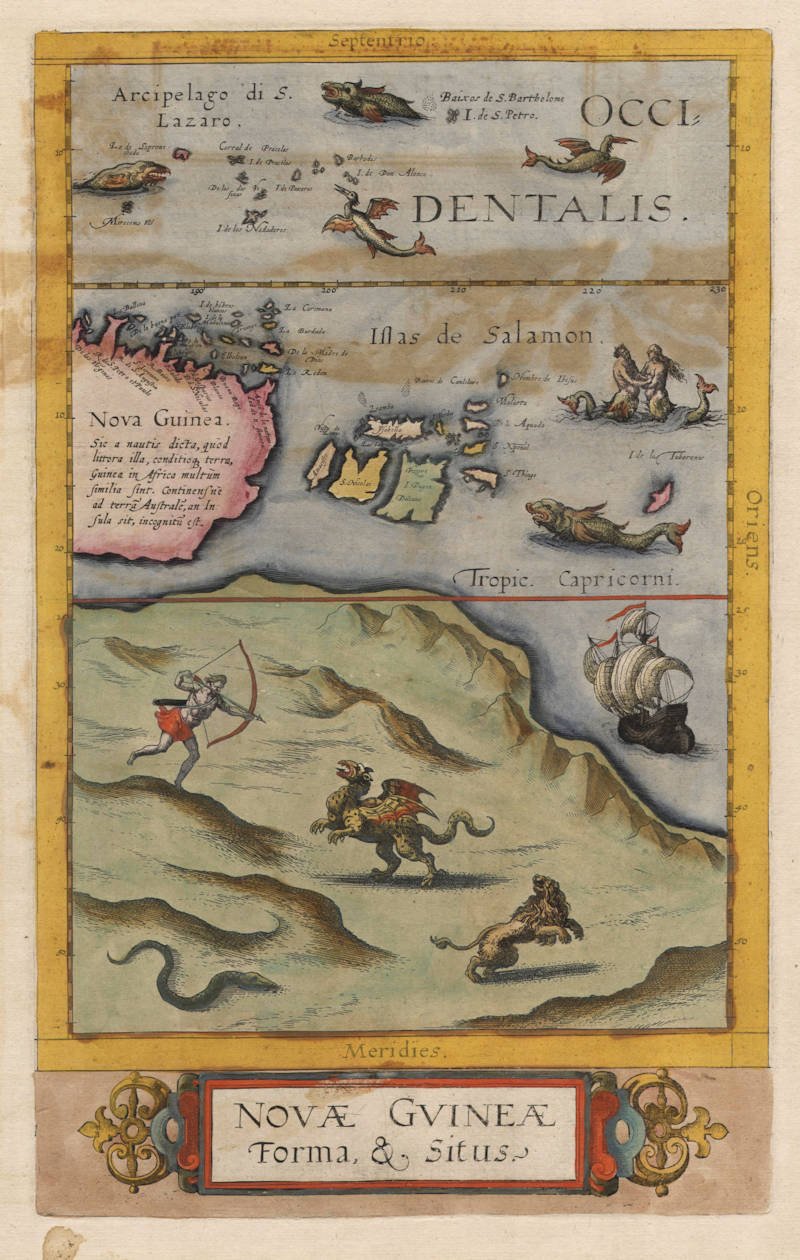

Novae Guineae Forma & Situs

Certificate of Authentication and Description

This is to certify that the item illustrated and described below is a genuine antique

map, print or book that was first produced and published in 1593, today 433 years ago.

January 27, 2026

Cartographer(s)

de Jode

First Published

Antwerp, 1593

This edition

1593 first and only edition

Size

34.5 x 21.5 cms

Technique

Copper engraving

Stock number

18640

Condition

some offsetting, else excellent

Description

Summary

In a way, this can be called the first printed map of Australia.

(Günter Schilder)

It may be called the first map of Australia.

(Ronald Vere Tooley)

De Jode's map holds a significant place in the history of the charting of Australia.

(Simon Dewez)

Often regarded as the first printed map of Australia.

(Susannah Helman)

Condition

Thick paper with no restorations or imperfections. Very wide margins all around. A crisp and very early imprint of the copperplate, with the text support lines still visible. Rare contemporary colour. Minor color offsetting from half sheet map which was opposite this map (Quivira Regnum). Small section with old reinforcement on verso. A very desirable collector's example.

Australia Unveiled

This map appeared for the first time in the second edition of de Jode's atlas Speculum Orbis Terrae, Antverpiae... 1593. Though the map is entitled Novae Gvineae, only the upper part shows New Guinea: the lower section shows a wholly imaginative mountainous, Australian north-coast. On it is depicted a dramatic encounter between a hunter, armed with bow and arrows, and a griffon, a lion and a snake. In a way, this can be called the first printed map of Australia.

The legend on New Guinea, apart from repeating the old complaint that it is not known whether it is an island or part of a continent, states:

New Guinea is so called by the sailors because those coasts, the nature of the country, are similar to the African Guinea.

The matter of New Guinea and the south-land is taken up even more extensively in the text of the atlas (fol. 12v [on the back of the map]):

This region is even today almost unknown, because after the first and second voyages all have avoided sailing thither so that it is doubtful even until today whether it is a continent or an island. The sailors called this region New Guinea because its coasts, state and conditions are similar in many respects to the African Guinea. Andreas Consalius seems to call it Peccinacolij. After this region the huge Australian land follows which - as soon as it is once known - will represent a fifth continent, so vast and immense is it deemed. In the east the Salomon Islands join up, in the north the S. Lazarus Archipelago; it also takes its beginning at two or three degrees south of the equator. In the west it is, if not an island, connected up with the Australian continent.

(Günter Schilder)

The lead up to the Dutch discovery of Australia

De Jode's rare map of New Guinea and Terra Australis Incognita is considered by some authorities to represent the first printed map of Australia.

One of the remaining contentious issues on the history of the discovery of Australia is whether or not the Dutch were the first European nation to land on Australian soil. Many argue that it was indeed the Portuguese who landed first. Some say it was a little known French voyage that should claim the prize.

De Jode's extraordinary map, showing New Guinea, the Salomon Islands and a large fictitious northern Australia, is frequently used to illustrate knowledge of Australia prior to the Dutch landing on the west coast of Cape York Peninsula in 1606. Tooley notes, 'It may be called the first map of Australia', while Schilder states, 'In a way, this can be called the first printed map of Australia'. Certainly the accompanying text lends weight to this viewpoint. The text from the atlas states

.... After this region, the huge Australian land follows which - as soon as it is known - will represent a fifth continent ...

As with Montanus' map [of the world], the depiction of an 'Australian landmass' here probably represents no more than the charting of the tip of 'Terra Australis Incognita'. Such a portrayal of the Southland can be seen on the 1570 world map by Ortelius. De Jode's map does however hold a significant place in the history of the charting of Australia.

The map is decorated with sea monsters, mermaids and ships. The large southern mainland is resplendent with a lion, griffin and a spear-hurling warrior.

Gerard originally issued his atlas in 1578 to compete with Ortelius' atlas with little success. In 1593, two years after his death, Gerard's son Cornelius re-issued the atlas. This map first appeared in that posthumous edition and appears on the same sheet as Quivirae Regnum.

(Simon Dewez)

Rethinking the southern continent

New Guinea and Polar hemispheres

From: Cornelis de Jode, The Mirror of the World, Antwerp, 1593.

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA, CANBERRA,

MAP RM 389 PETHERICK COLLECTION AND MAP RM 4350

Overshadowed by the power and success of Abraham Ortelius and his 1570 atlas, Antwerp's de Jode family nevertheless published two maps of great significance in the story of Australia's mapping. One, often regarded as the first printed map of Australia, shows New Guinea and the Solomon Islands to the north of a large, mountainous landmass populated by a griffin, a hunter and a snake. Both it and this early spectacular double polar view map appeared in Cornelis de Jode's extremely rare atlas Speculum Orbis Terrae (The mirror of the world) (1593), the second expanded edition of his father Gerard's atlas Speculum Orbis Terrarum (1578). Each edition sold relatively poorly, making the atlases and any maps taken from them quite rare.

Both maps are unsigned, making it unclear who was responsible for either. Though best known as an engraver and mapmaker, Gerard de Jode (1509–1591) was also a printer and printseller in Antwerp's flourishing trade. For example, he published Ortelius' 1564 world map. He also produced non-cartographical prints. He is known for producing prints, etched with a burin, that were made to look like engravings. Cornelis de Jode (1568–1600), on the other hand, was not a cartographer but an engraver, publisher and geographer.

The map of Novae Guineae (New Guinea) juxtaposes a fairly conventional treatment of New Guinea and the Solomon Islands with an unannotated southern land and seas filled with strange and mythical creatures. In this respect, it is reminiscent of the Dieppe School maps, themselves believed to owe much to now-lost Portuguese mapping. While most of the annotations, and all the accompanying text, are in Latin, several terms used are Spanish, including Islas de Salamon, the Solomon Islands. The representation of New Guinea has significant text, both on the map and on its reverse.

Text appearing on Nova Guinea explains that it was given this name by sailors because the shore was thought to be similar to that of Guinea in Africa. The mapmaker ends by stating that it is not known whether New Guinea is joined to the southern land.

One of two world maps in the 1593 edition, de Jode's twin polar view owes much to the world map of French Arabist scholar Guillaume Postel. Postel, like Mercator, allowed the possibility of a great south land, though he saw the Antipodes as part of a greater rethinking of the world along Biblical lines. Accordingly, he gave the continents names after the sons of Noah associated with them - Europe became Iapetia (after Japhet), Asia Semia (after Shem) and Africa Chamia or Chamesia (after Cham). Postel believed the south land should be called Chasdia, after the son of Cham (Africa), as he had heard it was populated by dark people. According to Posteľs account, For in that part of the coastline that has been discovered, men were seen of great blackness. De Jode's double hemisphere map follows Postel in calling the south land Chasdia and the mapping and other annotations are clearly derived from it. Most prominent in capital letters, however, are letters Ter. Australis incognita, thereby giving Chasdia secondary importance. Large and small islands labelled Iava maior and Iava minor also appear on the map making it clear that neither is associated with the south land. Polar views were popularised by Dutch mapmakers half a century later.

The questions over what informed these maps goes to the heart of debates about sixteenth-century European charting of the south Pacific. Were these maps purely speculative, or were they based on sources that no longer survive? And who drew and engraved them, if not Cornelis?

(Susannah Helman)

Gerard de Jode (c.1509-1591)

Cornelis de Jode (son) (1568-1600)

Gerard de Jode originally issued his atlas in 1578 to compete with Ortelius' atlas with little success. In 1593, two years after his death, Gerard's son Cornelius re-issued the atlas. The success of the atlas was very limited due to heavy competition with Ortelius, who also seems to have bought many copies of de Jode's atlas to take them off the market. Because of this, both editions of the de Jode atlas are exceptionally rare.

"Gerard de Jode, born in Nijmegen, was a cartographer, engraver, printer and publisher in Antwerp, issueing maps from 1555 more or less in the same period as Ortelius. He was never able to offer very serious competition to his more businesslike rival although, ironically, he published Ortelius's famous 8-sheet World Map in 1564. His major atlas, now extremely rare, could not be published until 1578, eight years after the 'Theatrum', Ortelius having obtained a monopoly for that period.

The enlarged re-issue by his son in 1593 is more frequently found. On the death of Cornelis, the copper plates passed to J.B. Vrients (who bought the Ortelius plates about the same time) and apparently no further issue of the atlas was published."

(Moreland & Bannister).

"After the death of Cornelis in 1600, the copper-plates came into the hands of Jan Baptiste Vrients, then the publisher of Ortelius' Theatrum. Apparantly Vrients must have bought them to prevent any further publication of the Speculum."

(Koeman)